Sustainable city design is gaining more attention as the world looks for answers to humanity's challenges on Earth. However, history shows that the pursuit of utopia often ends in failure. Come along with us on this long-read, diving into remarkable utopian cities from past, present and future. Discover how the key to success in sustainable city design is to learn from the mistakes of the past, avoid hubris, and to focus on the systemic aspects of how to make resilient, regenerative cities that can adapt to changing conditions.

In this article, we explore a range of historic utopias and use their failures to learn which guidelines a sustainable city needs to follow. This article looks at several examples of historic utopias, including Brasilia, Masdar City, NEOM the Line, Almere, Toyota’s Woven City and the Garden Cities, and extracts several key lessons from these failed utopias. Let's dive in and start exploring the world of 'utopia' and its history of many disasters, few successes, and plenty of lessons.

This article was written together with the historian Saul Boyle over the course of 2023. Discuss the article together with us on LinkedIn.

A world in crisis obsessed with Utopia

The world is asking increasingly for more fundamental answers to humanity’s plight on this planet, and sustainable city design is right front and centre. We’re saturated with imagery of green towers in fields of solar panels and curvy futuristic buildings among a web of flying or autonomous electric vehicles. As we get swept along, we wonder, are these utopias actually the right way forward? Are gleaming glass towers, floating metropoli, ball-shaped farms, and hundred mile long high tech cities actual answers to the challenges we face? Or are they disasters waiting to happen?

As usual, history has a thing or two to say on the matter. The fascination and striving for Utopia is nothing new. In this article we, Saul (historian) and Tom (sustainable city designer) explore a range of historic utopias, learn from their (often) utter failure, and use these to formulate guidelines to aid us in building our sustainable city framework, Orchid City.

We’re in luck. In the search for failed utopias and disastrous ‘smart-cities’ and the like, we don't have to look very far. We humans have spent the last century or so thinking about and then designing and building some spectacular failures in our games of playing God with city design.

Fueled by the power of industrialization, it became increasingly possible to plan a whole city from scratch, rather than let it slowly develop. And of course, humanity wouldn’t be itself if it didn’t push this feat to some remarkably ridiculous heights of hubris. Today, the city, as a concept itself, has become a primary battleground for sustainability efforts; as it is here that all our challenges around climate, resources, ecology, justice, and the economy, all come together in one place. As the world becomes increasingly urbanised, the city has again become the object of intense speculation, discussion and thought.

And once more, the playground of some really bad ideas. In our journey here we take you to look at utopian city designs such as Brasilia, Masdar City, NEOM the Line, the Garden Cities, as well as lesser known examples such as the city of Almere and Santander.

But more on those failed eco-cities later. We begin with a story of a unique, Black Swan, event a bit longer ago, one of Saul’s favourite stories. No one could predict that a giant fire would fuel innovation in city design. But we start with just such a thing.

The Dreams of the Fire

On Saturday September 1st 1666 a sudden and vast fire swept through the City of London. What had begun as a small house blaze in a bakery that supplied the King's household, down in the crowded, foetid streets around the river docks, then took advantage of weeks of dry weather. The fire was further fueled by a strong easterly wind and 17th Century ideas of fire prevention, and began consuming the entire building and those around it.

Four days later, four fifths of the city had been consumed. Over 13,000 homes had been obliterated, each one containing a multitude of citizens now made homeless. 44 of the great livery company halls had been put to the flame. 87 churches. The great cathedral of St. Paul's. The Royal Exchange. From streets upon streets of small wooden framed homes, to the towering edifices of state buildings; all reduced to smoking piles of stone and timbers.

The city appeared, in all the ways that mattered, destroyed. This disaster, catastrophic for many, also sparked a surge of creative ambition among architects and visionaries. The city, now a blank slate, beckoned for a rebirth as a City of the Future.

From out of the ashes

Christopher Wren, a rising star in architecture, was quick to propose a new London, drawing inspiration from Paris and Rome. His vision was for wide avenues and grand piazzas, a cityscape that married the spiritual majesty of St. Paul's Cathedral with the worldly allure of the Royal Exchange. Wren's plans reflected a growing trend in urban design, emphasizing grandeur and formality as symbols of power and wealth.

But Wren wasn't alone in his architectural dreams. Valentine Knight envisioned a city built on practicality, proposing a grid of streets intersected by a revenue-generating canal. His idea, though modern, was met with royal disdain and personal misfortune.

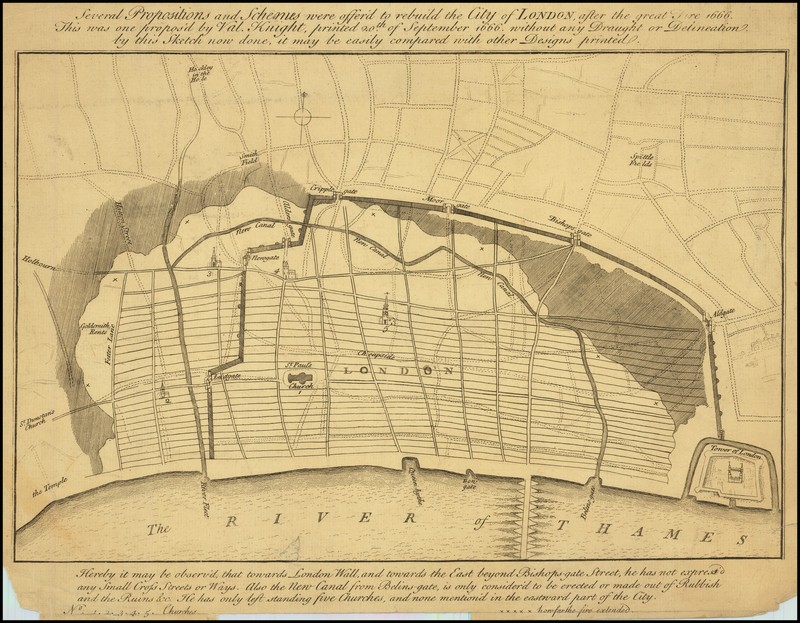

Proposed City map of London by Valentine Knight

Alas for Captain Knight, he unwisely suggested that the canal could charge a toll, allowing the King to make some money from the enterprise. His Majesty objected to the presumption that he needed the money, so he had Knight arrested. From Knight’s plans we see a focus on mass logistics and economics as the backbone of a city, which is still a dominating factor in most of today’s city planning strategies (and a frequently failing one, but more on that later).

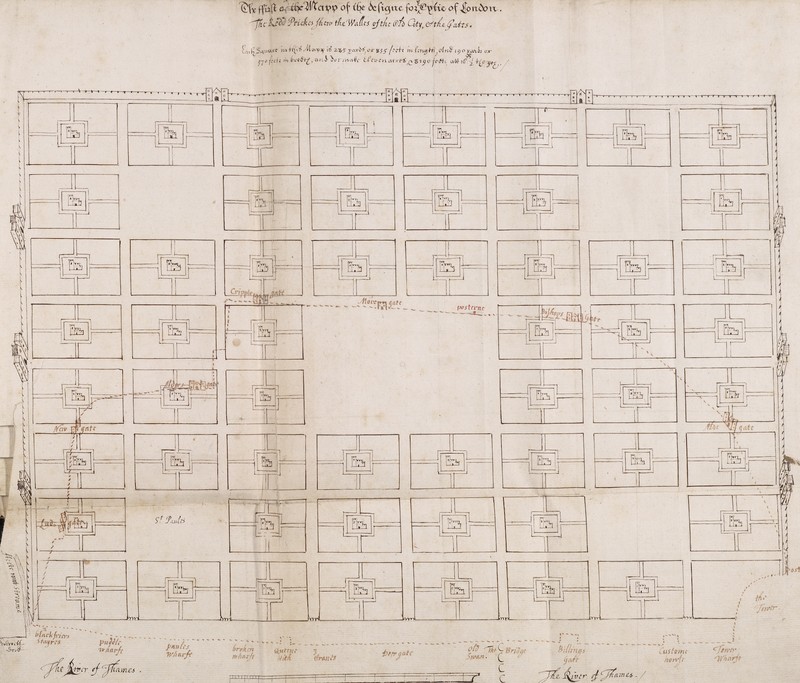

Plan for London by Richard Newcourt

Richard Newcourt, on the other hand, imagined a city of human scale, focusing on small public squares surrounded by civic buildings and residences. His concept hinted at the benefits of walkability and community connectivity, principles gaining renewed attention in contemporary city planning. His plan for the city was all about scale, and he began his ideas with designing a single small public square. At its heart would be a church, around the church local civic buildings would be arrayed, and beyond them would be the houses and shops required for residents. The square would be the centre of a new 'block' or neighbourhood. His idea was you could do this once, and then build another one next to it, and one next to that, and so forth, composing a city out of blocks of identical squares.

Newcourt's plans were obviously not adopted, although some suggest his ideas were the foundation upon which Philadelphia was based, the city which became the progenitor of the American city grid system. From Newcourt’s plans we see an insight into an understanding of the benefits of adopting human scale in zoning and scaling, increasing walkability and community connectivity, aspects which are making a re-entry into modern sustainable city design.

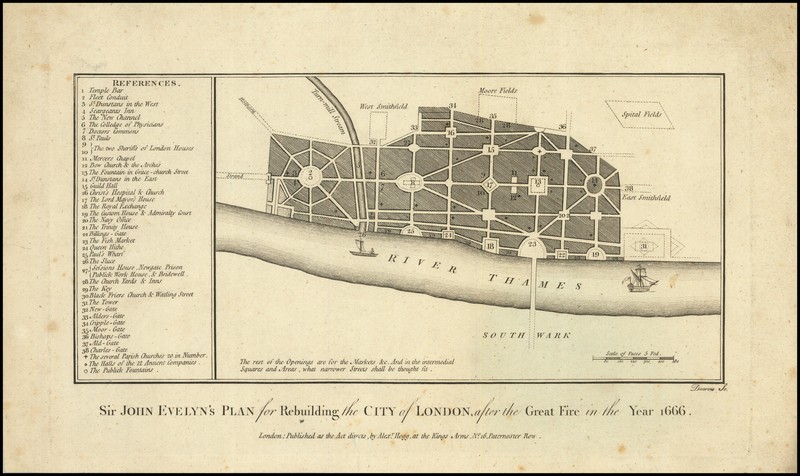

Plan for London by John Evelyn

John Evelyn looked to Italian cities for inspiration, imagining London with stone-covered piazzas and broad avenues based on radial planning. These diverse visions collectively showcased a spectrum of ideas about what a city could be, each architect imprinting their unique perspective on the future of urban living.

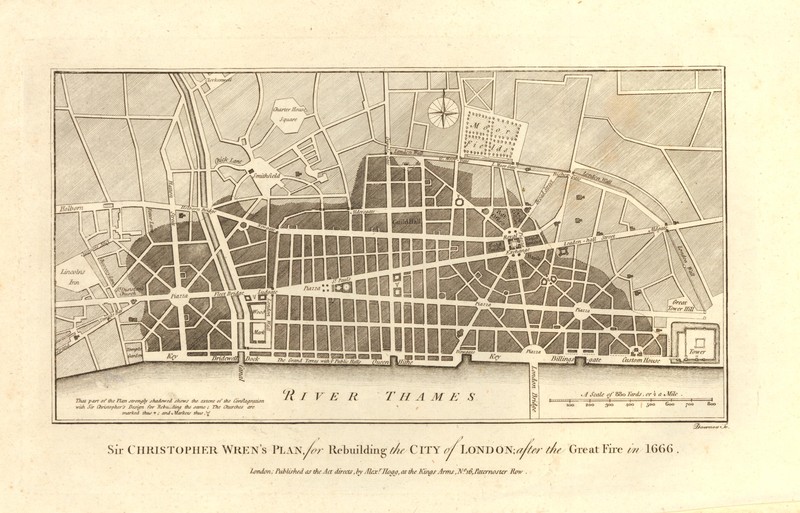

Plan for London by Christopher Wren

Wren’s plans demonstrate a growing fascination with grand iconic architecture and formalised city planning as a display of power and wealth, which much modern urban planning is yet to progress from. These aspects can clearly be found in many industrial and contemporary planned (and often failing) city designs, such as Dubai.

Without question, this was the most visually stunning and beautiful of all the designs submitted to King Charles II as October 1666 dawned.

Of course, not one of them would ever be used.

When we seek why, the standard explanation is that the crown never had the money to pay for such things, or that there were issues with the rights of landlords and who owned what in the complicated city. But the actual reason was more simple.

The residents of London, without fanfare, protest or so much as an 'excuse me', began to rebuild their homes in roughly the same spots and in roughly the same places.

The King's new regulations saw that all new buildings in London were to be built in stone at least to prevent a repeat of the fire; but London, its residents, the beating life blood of the mediaeval city, didn't want to rebuild the place with grand piazzas, toll canals, and long avenues. They wanted their homes back. While the buildings were new and up to the crude basic new building code, the city fabric returned to what it was. A few wider streets here and there, but the system itself was too robust to be defeated by something as violent as a fire or as ambitious as a King's vanity.

In short, London had never been destroyed.

Buildings had been obliterated, but London showed that a city isn't its majestic structures, or its stately avenues; London in 1666 proved that a city is more than just a place which people fill up. It is the people who make a city, who ARE the city. It is the people that form and manifest the city’s fabric. The vital human element may have been what caused the fire, may have been too blind to the importance of fire prevention and whose choices had allowed the city to be burned in the first place, but it was also that powerful, complex human agency that had caused the ambitious plans of visionary architects to be scuppered the way they were. In many ways the residents of London in 1666 were advocates of one of the great maxims about utopia; it is the people that make or break the city.

Just because something looks good on paper doesn't mean it's going to be a good place to live in.

With that lesson in hand, let’s look at why in the last few decades, the once rather rare situation of whole-city design has become more and more prevalent.

City design as the well appointed road to hell

The historical lesson of urban planning's failures is often overlooked. In the 20th and 21st centuries, we've witnessed numerous attempts to create 'Cities of the Future,' yet many have failed. This trend reflects a shift towards grandiose designs and technical marvels, where the essence of individuality and practical urban living is frequently overshadowed.

The power of industrial, digital, and economic revolutions has concentrated in the hands of a few, enabling the rapid conceptualization and construction of entire cities. These projects often dazzle with futuristic imagery and promise innovations like data-driven infrastructure, autonomous vehicles, and advanced urban farming. However, the allure of these concepts often masks a critical oversight: the intricate, subtle details that make a city truly functional and livable.

The pursuit of creating the 'City of the Future' has become a mantra for architects and planners, driven by global challenges like climate change and urbanization. This has spurred numerous architectural competitions, showcasing stunning designs more focused on aesthetics than practical urban planning. Yet, these ambitious projects frequently result in monumental failures, revealing a lack of understanding of what constitutes a successful, sustainable city.

Grist's article on Masdar's failure

We're not suggesting that every futuristic city concept is doomed. However, the likelihood of success is slim unless these designs are grounded in a holistic understanding of urban growth and functionality. Most of that can be sourced back to the root of the problem, in that a good city isn’t so much created through a physical design by one or a few people, but that it is a development process, continuing changing and adapting itself over the years. Looking back over the last century, the various Cities of the Future are an elephant's graveyard of the best of intentions, which line their immaculately presented boulevards to Hell with their magnificently designed but ultimately failed dreams. Cue projects like Fordlandia, Masdar, and NEOM. Let’s look at a few.

Alaskan Folly: Seward’s Success

Image: Popular Science Magazine

The most basic mistake of utopian city design is assuming that plans on paper translate into something workable in reality. Sometimes the ideas never even get off the page, often because what’s on the page has lost some footing with reality. Ambitious and visually stunning dreams that are born in the imagination, and die there also. Places like Seward's Success. Seemingly straight out of a Star Trek set design, straight into Alaska. Or, well, almost.

In 1968 the discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, prompted the need for thousands of workers to possibly move to one of the more isolated and somewhat environmentally harsh places on Earth. Tandy Industries of Tulsa, Oklahoma, immediately came up with a novel and visually striking solution.

The $170 million ($1.3 billion today) initial phase of development was to create an entirely enclosed city (under glass to begin with), providing homes to the first-wave of 5,000 residents, It would also contain 55,000 m2 (600,000 sqft) of modern office space, over 27,000 m2 (300,000 sqft) of retail space (as a mall with residences) and even an indoor sports arena. At its heart was the grand ‘Alaskan Petroleum Centre’, a 20-story tower block which was to be the hub for the various oil companies alongside the oil service providers.

Alaska is a cold place. But, in Seward’s Success, people would live at a constant and balmy 20°C (68°F) year round temperature, maintained by both the glass roofs creating a greenhouse effect, coupled with heating from natural gas extracted from the area. It was planned to eventually house a population of 40,000. The residents would travel around in monorails, sky trains, along elevated bicycle paths, and moving walkways. This was cutting edge late 1960's technology here.

Of course it never got off the ground. When legal action held up the trans-Alaska pipeline, the subcontractors couldn't maintain the lease on all of the land and the whole project was halted and died. Because it was one large connected system, to be built at once and succeed at once, it all failed at once. A dream that never was to be, we can't even say if it would have worked as it wasn't even able to get itself built.

The First Lesson: Utopia has to be grounded; trying to build a new paradigm for society is hard enough, it needs to ensure it can be phased, to work in parts as well as a whole, built in stages, without additional difficulties having to complete the whole system of society in one go.

Octagonal thinking

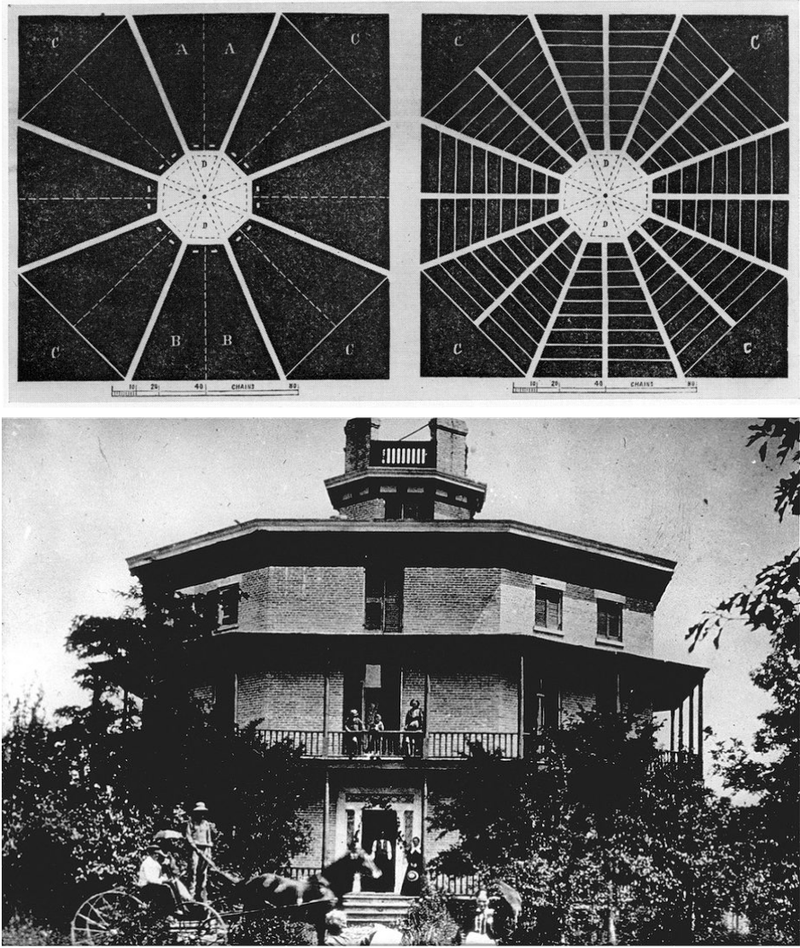

Images: Library of Congress

Way back in 1856, it was the vision of Orson Squire Fowler, whose 'scientific' belief that the octagon was the ideal shape to build a city block around, which led to the creation of the grandly named Octagon City in Allen County, Kansas. His visionary ideas inspired a trio of entrepreneurs, to form something called the Vegetarian Kansas Emigration Company, intended to create a utopian city of the future there in this newly opened territory. While they had originally thought about taking Fowler's octagonal ideas and creating an exclusively vegetarian community nestled on the southern side of the Neosho River, they eventually decided to integrate vegetarianism into a wider, more inclusive, ideal moral community at a larger site to the north of the river.

The city was to be filled with the people who had agreed to a high moral commitment; all prospective residents had to take oaths about maintaining strict proper behaviour, and agree to educate their children in strong moral virtues. Such bold people needed a bold living space, and this is where Fowler's octagon's came to the fore. Octagon City would be centred on an octagonal town square (wherein the civic headquarters would of course be based) from which would radiate eight roads outwards.

In-between these roads, in an area of around four square miles, 64 highly moral families would build their octagonal farmhouses with octagonal barns. It was an (octagonal) Victorian Era vision of the future. And unlike the previous example? It was at least started.

However when the first 100 settlers arrived at the isolated location, they found it had intentionally been placed away from the 'corrupting influence' of others. This meant the nearest source of supplies and goods was 50 miles away. They were somewhat disappointed by what they found. Rather than the octagon shaped town square, or even the promised and much required grist mill and sawmill to begin construction with, they discovered the only building was a single, suspiciously rectangular, log cabin with dozens of tents for newly arrived families. And only one plough.

The project died within a year, the moral community ravaged by malnutrition, mosquitoes, malaria, and monsoon-like deluges caused by huge thunderstorms. Within a few weeks the spring which supplied them with water dried up. In time many of the residents fled to the nearby Osage Native Tribe and by 1857 only four residents remained. Octagon City has left no trace of its failure.

There’s two distinct lessons to be learned from this, also regarding the failure of many utopian communities built on particular belief systems in the last 100 years.

The first is that a true resilient community embodies diversity. A community does not work well when there’s only people with a very particular inkling clustered together. No matter how tough and determined these people are, if a community is to succeed, it needs to attract, house, and foster a diversity of people. A true city does not have a target audience. This is something we’ll get back on later.

The second is that communities are incredibly hard, if not nearly impossible to build entirely on their own. Humanity gains its strength and resilience through its interconnected social and economic relations. Cutting off a community on purpose is to start with two hands tied to your back. Autonomy is worth striving for, but this striving does not need to go hand in hand with total isolation.

Levasa: the hills of Pune

Image by Yashika Chhabaria

Examples of cities being conceived and built because rich men decided that their wealth gave them some magical ability to know how to create a city is not just a Victorian Age folly. We can see the 21st Century equivalent of Octagon City in the hills above Pune in India. It was here that Indian millionaire Ajut Gulabchad conceived of a city of the future to be built in the lush countryside, capitalising on India's ambitious plans to build '100 smart cities', in 2015.

The city, called Levasa, was supposed to be based on the romantic city of Portofino in Italy, with 250,000 residents living in 18 linked villages across 10,000 hectares of land. Many invested large sums of money into the project, and you can today see what appears to be a well organised township nestled in stunning monsoon greenery. However Levasa became a miasma of public spending, a sinkhole for public services, and is now a ghost town, filled with buildings being reclaimed by the green- all in less than a decade. The lawsuits, litigation and petitions to the Indian government by investors and recriminations are still active, and like Octagon City, Levasa seems doomed to become no more than a cautionary tale.

The Fourth Lesson: Wealth, no matter its size, is no indication of merit when it comes to building Utopia. Just because there is a lot of money, does not increase the success rate of a sustainable city by a significant amount. If the fundamental operation principles are not sound, no amount of capital can save a city.

If we were to seek out the ultimate example of a city conceived by one rich man's folly, and which was actually built entirely, then one need only travel to Brazil, to a location deep in the Amazonian rainforest. Here was a city conceived by and built by none other than Henry Ford, and like Octagon City and Levasa, stands as testimony to hubris and proof of how ideas that work in one part of the world, may fail miserably in another.

Fordlândia

Back in the 1920s, Henry Ford, not anyone less than the famous automobile maker, sought alternative rubber suppliers to reduce costs for his tires. He settled upon the idea of creating his own massive rubber plantation, staffed by his own people. In time Ford gained an agreement from the Brazilian government to utilise around 2.5 million acres of land in the northern rainforest region for a rubber plantation. He would be exempt from all export taxes provided he paid 9% of the profits of the project to the municipalities.

Ford's plan was for a small part of America to be fabricated there in the middle of the jungle, with clear segregation for the Brazilian workers and their American managers. They were all to live in their own modern American styled homes. Ford had wanted the area to be self-sufficient in social needs so alongside the rubber plantation and residences was planned a school, a library, a hospital, playgrounds, a swimming pool, a hotel and, of course, a golf course.

Work began in 1926, instantly running into logistical issues, such as non-existent infrastructure, challenging logistics and diseases which decimated the workforce. There were no roads to the site, and it could only be reached via the Tapajós River.

The difficult construction took two whole years, finalised when Ford sent two merchant ships packed to the brim with American finishing touches, everything from the door knobs to be used on internal doors to the town's giant water tower. In 1928 the town of Fordlândia was opened. Offering good wages and 'modern living', Ford quickly found a working population from nearby cities and the serious business of rubber cultivation could begin.

Employee Housing at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1930-1931 (Photo: From the collections of The Henry Ford)

It was a disaster almost from the moment it started.

Ford, while a genius at mass producing cars to scale, had no idea how to cultivate rubber, and due to the local climate, tapping the latex in the trees had to begin at around 5am. It was going to be hard work for whomever was involved.

The life of the workers was completely regulated in a way none could have imagined; they were given unfamiliar food, such as American hamburgers and canned goods, and forced to live in the newly built American-style housing. They had to wear ID badges at all times, and were also forced to keep American work schedules; so as well as starting at 5am, they would have to work through the middle of the day. This was under a tropical sun.

What didn't help was that Ford imposed strict rules of behaviour upon his workers, based on what we can only possibly imagine were Ford's ideas of what made America great. Alcohol was banned (this was the prohibition era), but so was tobacco; all non-married women were banned from the town and he even disallowed the playing of football. These rules were to be enforced even in the workers' own homes. He hired and employed 'inspectors' to go from house to house to check how organised/neat the houses were and to enforce his ideas.

The residents appeared to comply but the inspectors soon realised that a growing trade in contraband items was being smuggled in by workers paddling down river to merchant riverboats who, for a small fee, would happily hide banned items inside large watermelons. In time about 5 miles upstream, on a small island in the river, named the 'Island of Innocence', a little community of bars, nightclubs and brothels emerged, catering to the somewhat captive residents of Fordlândia.

All of this wasn't enough to fully reduce the tensions of trying to exist inside Henry Ford's weird dream of American utopia. In 1930 the Brazilian workers finally had enough, oddly enough the breaking point was over food. In the town's cafeteria, after having been served another helping of a processed American meal, they erupted in anger (known locally as the 'Quebra-Panelas' or the Breaking Pans revolt).

The workers quickly cut the telegraph wires which allowed communication in and out of the town, before driving out the American managers and kitchen staff, who had to hide out in the rainforest for a few days. Eventually the Brazilian army was sent, and the whole thing ended peacefully with new food arrangements being made by the managers (presumably meaning less processed American food).

Meanwhile none of Ford's managers had any experience of growing rubber trees, and as such didn't know that rubber trees in the wild grow a distance away from each other, to prevent plagues and disease. Which explains why the rubber trees in Fordlândia were planted close together. Which created an ideal climate for leaf caterpillars, suava ants and tree blight. Eventually these issues, coupled with the overall ineptitude of the very idea, saw the Ford Motor company abandon Fordlândia in 1934.

Laborer’s House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931 (Photo: From the collections of The Henry Ford)

Henry Ford’s true legacy is that he managed to ignore all earlier stated lessons of creating a utopian society simultaneously; wealth thrown after a fundamentally unsound plan, cultivating a target audience in the city, and trying to erect a full system from scratch. It is a measure of his stubbornness and his excessive cash that it lasted as long as it did.

Yet, the examples of Fordlândia, Levasa, Octagon City, and Seward's Success are merely just projects where half formed ideas of city planning based on grand assumptions fuelled by populist or imaginative solutions failed at a most basic level. These are not as bad as when people actually design and successfully build their utopian dreams. Once over the initial hurdles of creation, some of these ‘cities of the future’ face degrees of problems that may not make the city become a ghost town, but certainly doom it to being unsustainable as a place to live, often requiring decades if not centuries of slow, expensive fundamental repair, meanwhile enjoying sub-optimal living conditions.

Garden Cities: Paternalistic Gardens’ of Eden

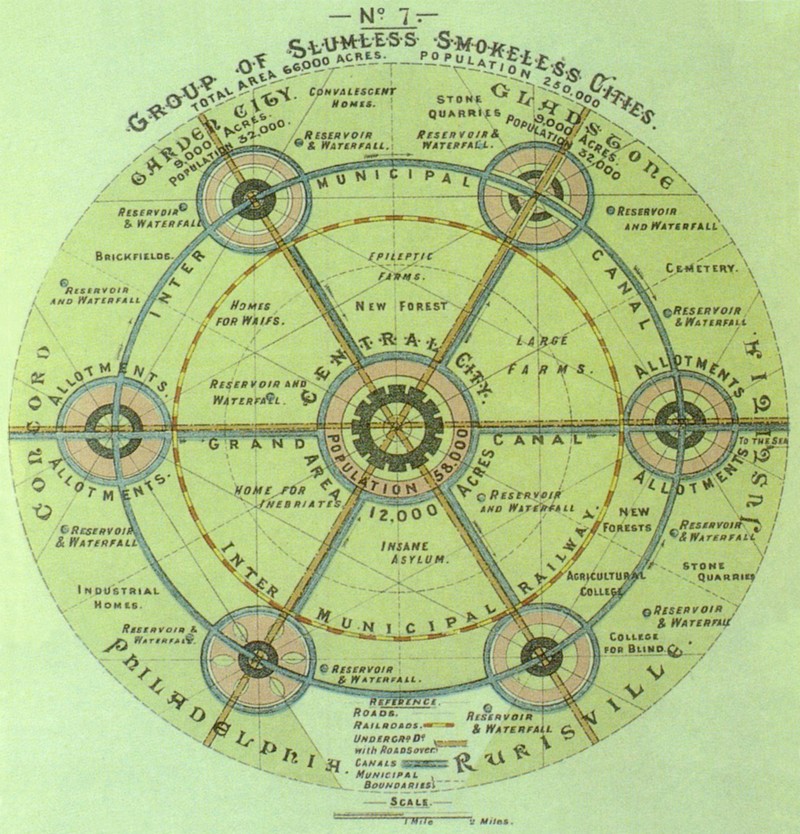

Garden Cities were the brainchild of Ebenezer Howard, who first postulated the idea of new cities mixing countryside with urban living as far back as 1898. In time this led to a full blown Garden City movement, seeing the development of the town of Letchworth in England, the London suburban development of Brentham Garden Suburb and finally, Welwyn Garden City also in England.

Howard, like Fuller and Fowler, was a visionary. He conceived his ideas in a time when cities such as Londen and Manchester were becoming dangerous, unhealthy, coal-smoke covered and congested places to live due to the factories of the industrial revolution. He saw cities based around form rather than function. In his mind, an idealised garden city would house 32,000 people on a site of about 9,000 acres. He originally conceived of concentric patterns with open spaces, public parks and even six massive 36m (120 feet) wide radial boulevards extending out from the centres. He pictured his garden cities would be self-sufficient, with the idea being when one reached full potential, another would simply be built nearby. For Howard, eventually he could see a cluster of garden cities all surrounding some central city, each linked generously by road and rail.

At his heart however, Howard hated cities, and in his writings you get the impression that there is a universal agreement that cities were overcrowded and civic authorities could not maintain them any more. Howard quotes numerous respected thinkers of his age, all of whom shared his disdain for the vulgar cities they saw all around them. Howard's Garden City concept wanted to combine the benefits of the town and the countryside, to provide the nation's working classes with an alternative to the binary choice of living in an overcrowded, foetid city or being forced to return to rural lifestyles and farm work. Not unlike today’s challenge surrounding our cities.

This paternalism, while well meaning, was a very strong and a powerful Victorian virtue that ran throughout his entire idea. This wasn't, despite his claims, a practical response to the issues raised by the growth of cities. This was a moral movement, in its own way as ill conceived as Henry Ford shipping an American water tower to the jungles of Brazil.

The ideas, however, struck a chord, not just in England. As well as the towns in the UK built around Howard's ideas, garden city design elements were built in America, Canada, Brazil, South Africa, Australia, Argentina, Belgium and even influenced the principle design features of Christchurch in New Zealand and Tel Aviv in Israel.

Haveforeningen Harekær, Brondby, Denmark. (Photo: Google Earth)

Yet, while they were adopted with gusto, garden cities proved to be another crucial proving ground of the maxim that 'what looks good on paper doesn't always translate to reality'. While the merits of dealing with overcrowding and the dehumanising effects of living in and around industrialisation were positives, it was built upon some very bad ideas. It did not help that in their desire for greater ‘liveability’ (sustainability?), back then, as often as now, they did not define the exact meaning of what performance goals the garden cities hoped to reach. And without a clear goal, it rarely achieved universally positive outcomes.

While they were supposedly about bringing people closer to nature, building the garden cities meant the destruction of large amounts of nature to begin with. New lesson number one, don’t fight or destroy nature. Howard never realised that nature wins over technology, and so his version of natural environments were never as efficient or as good as the actual natural environments they had to dig up to build the Garden City upon. Their isolation meant they were not always a net positive to the economy. Later the recent movements towards embracing urban density shows how garden cities' basic ideas were subsumed into a wider range of suburbanization models, which are often found to be problematic.

Garden cities were found to suffer from on-the-ground failures that the plans simply did not foresee. Ideas that look good on paper resulted in ghettoised communities and escalating crime. In 1998, the architect responsible for introducing garden city ideas into Australian public housing admitted that the first suburb he had created had failed as "everything that could go wrong in a society went wrong." In time "it became the centre of drugs, it became the centre of violence and, eventually, the police refused to go into it. It was hell."

The next lesson; Nature wins over technology. One can only work with it, not against it. This is not the worst example of this, far from it (lower down we discuss the failure of Masdar, the prime example of this mistake) but at its heart the Garden City movement is an example of this. Another major planning misstep is that the Garden Cities demonstrate a lack of diversity, due to it being planned for a specific target audience. In addition to this, Garden cities are a form-over-function idea; circular communities built in a certain shape rules over everything else. We’ll see how bad that lesson gets when we get to the example of Brasilia further down.

Almere: How the very sensible goes very wrong

Almere from above in 2016, Photograph by Milliped

The Australian Garden City example cited above isn't the only time we hear architects regretting the spaces they have created for people to live in at a later date. One of the more overlooked examples of "regrettable planning", and a very powerful one, took place around the Dutch city of Almere.

Officially it is the Netherlands newest city, conceived as a feeder for Amsterdam, with the first residents moving in in 1979. The land the city is built on was reclaimed from the sea over a period of decades, becoming available in 1968. This "new land" led to a host of utopian plans and programs over the course of the following decades.

Almere's city plan was designed to mimic a ‘green’ way of living, avoiding urban densities, around a set of smaller nuclei. The centre of this all, poignantly, being a lake, following the idea that the city should not have one center. The city was designed carefully, with spaces allocated for residences, for parking, for shops and business. It was in all ways an example of modern urban planning. Well intentioned city planners simply wanted to build a nice place for people to live in, affordable, with lots of green, a lot of space for kids to play, and a lot of affordable housing.

Otherwise, the city did not have lofty goals, it was supposed to be an example of down to earth, rational thinking. Efficiently funded and managed, as Dutch projects tend to go, it was quickly built and inhabited.

The complaints began soon after families started moving into the area. Most crucially they were complaints about how badly the place worked as a location to exist in. Residential streets went on endlessly, hundreds of identical homes in endless rows. In a country famous for its bicycles, those living in Almere had to adopt the daily use of a car. The lack of a centre created a lack of density for services, shops closed, and few spaces where the community could connect, worked. The city planners reassured everyone, it would be fine. Give it time. Allow the saplings they planted become full blown trees, allow people to adjust. For the best part of twenty years the designers and planners assured residents that if you just gave it time, eventually Almere would be an idealised little city.

It was finally in 2004 that the men who designed Almere travelled there and walked the town themselves. And realised the entire thing was... awful. It was rigid. Cold. Monotonous. What had been simple marks on a piece of paper had turned into straightjackets, forcing residents to conform to some urban planners ideas while preventing the natural and normal growth of a city. There was a dizzying uniformity, red brick as far as the eye could see, and virtually no opportunity for either the individual or the community to express itself. The city prevented the community from forming, and the community to in turn from its own surroundings. It prevented the natural diversity a city should foster to thrive. It was a factory for living in.

In a documentary I watched in a Dutch architecture museum as a student, I witnessed the moment where the original designers just walked around the city they created, profusely apologising along the way. Oh my, this wasn’t what they had intended when they designed it! It was a walk of shame.

A visitor to Almere today will not find a blighted city, or a ghost town. There are plenty of people that enjoy living in Almere today, to which efforts to increase diversity and steer away from the initial anti-urban ideas have helped. Ironically, a centre-like area has been created to try to offset some of the more fundamental flaws of the 'centre-less' urban plan. A centre however, that today is still sparse with people and devoid of community influence, lined with chain stores and hard covered surfaces with the occasional stray plant. The 'center' struggles with low density, its hard lined artificial landscape, and lack of character. Efforts continue to spruce it up, and it's clear Almere is here to stay, so these efforts are worthwhile, although they could benefit from a more fundamental understanding of its foundational flaws.

Almere's quality of life is decent these days, if you own a car, and don’t mind being isolated, that is. For some, that is lovely; a quiet and affordable place to live. For others, it's an existential nightmare. This does the diversity of the town no good, for which the city tries to build new areas to compensate. Almere continues to struggle with its mobility, monotony, and deserted streets. To us, Almere feels like a cultural desert that needs to struggle too hard to overcome its basic structural faults. But it’s not too late to save it.

This is why Almere is so crucial and brings us back to our central point. Centrally planned cities that depart from a single vision defining their fabric inevitably fail. Forcing a limited diversity, forcing a lifestyle, and preventing organic development, is a recipe for any urban plan.

The Fifth Lesson: Treating the design of a city like the design of a building or a machine, and not like an organism that needs to be able to grow, change and manifest itself, results in poorly functioning places at best, and utter failure and collapse at worst.

Thinking in architectese

Image Copyright Natura Futura Architectura, from the Best Architectural Drawings of 2020

Let’s interrupt our review of example cities with some thoughts on why these design failures happen so often. Among others, it has something to do with how designers are educated, which is in turn a reflection of how we as a society have been thinking, for the last few hundred years specifically.

When an architect designs a building, they need to employ a reductionist, bottom up approach to the process. While a building is a complicated thing, it is a clearly defined system. You cannot leave parts of your design vague or undefined. You cannot just say the elevators will go in one part of the building and then leave a large space elsewhere blank 'just in case' the users of the building wish to relocate the elevators at some time in the future. That would be silly. A building must have clear and defined parameters. All systems within it, from air conditioning, to electrical wiring, to water piping, to stairwells, to foundational supports, must be clearly marked and broken down. Each part is identified and codified.

But taking such a reductionist approach towards planning something as complex as a city will always fail. Because reductionism cannot work alone in a complex entity like a city, which needs to adapt itself over time, proving to be resilient towards the future. A city needs to grow, its community needs to form, it needs to work with and allow nature to take its own path over time. All things that are not design-eable as you would a building. As the example from Londen has shown, buildings may change, but the city fabric of a city tends to permeate. It is not the bricks that make the city, it is the community, the (ever changing) economy, and the fabric that it manifests that does.

Indeed, this seems to be the core as to why many urban planners' dreams are dashed on the rocks of reality. Especially cities designed by architects instead of more holistic thinking urban planners. It is in our education system, where urban planning often ‘lives’ inside the school of architecture that the beginnings of this problem occurs. A city, indeed any urban space, is a complex, dynamic system. Change is written into its very DNA. Change over time. It is an axiom. And it is the lack of such realisation that can and will cause 'cities of the future' to fail. Architecture is as suitable a profession to design a city as a hairdresser is to be a psychologist. Furthermore, in the process of planning a city, it is often striking attractive artist impressions, with sweeping buildings and attractive vistas that juries and city governments base their decisions on. However, these images are grossly misleading, as a well functioning city is not primarily an aesthetic design.

So, when it comes to planning cities of tomorrow, we begin to now see the twin problems arise to confront our expectations. The first is the belief in grand schemes, often (but not exclusively) personified in allowing rich men build residences as they see fit. The second is that you have genuinely intelligent and brilliant architects labouring under the idea that when planning a city it should be done via the same identical thought process as designing a building.

Ville Radieuse: The father of eerie feelings

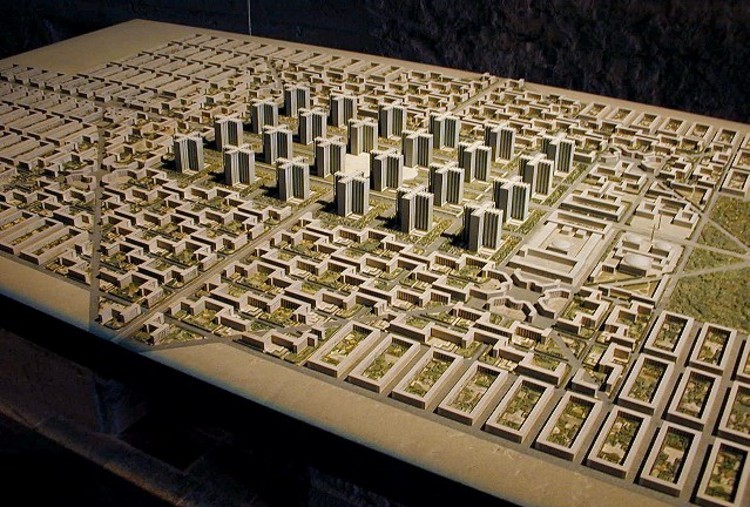

Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier 1925, Wikimedia

Examples? Well, the most obvious is Le Corbusier's vision of Ville Radieuse. The champion of purist architecture, he imagined a city filled with massive skyscrapers, in which both rich and poor alike would live. Separated by spacious parks and green spaces, all carefully divided into zones for work, or for leisure. The skyscrapers would be designed to let in sunlight and air, with rooftop garden spaces and catering and childcare in the basements.

Few utopian city ideas have had such a great effect on our society as Le Corbusier’s ideas. His ideas became ingrained in the architect community when Europe, recovering from the devastation of the second world war, needed efficient ways to rebuild large housing areas, embedding social ideas about equality, modern living, and healthy urban communities. They offered cheap and fast construction options, while catering to the ideas of democratisation of cities, affordable and modern living for all. “Machines a habiter” - Machines for living, as they were called, which back then was seen as a good thing. Now, looking back on them, we know better.

No working example of Ville Radieuse was ever built exactly, but these ideas formed the foundation of thousands of (often social) housing districts around Europe first, to be adopted around the world soon thereafter. Yet, not without criticism already from early on. One critic described the resulting idea as "buildings in a parking lot”, and where these ideas have been adopted, the large open spaces became instant no go areas, wastelands shunned by almost all, breeding crime, waste, and desolation.

Make no mistake, the need for decent housing for millions of people around the world has been supported by these ideas, which certainly contain important, valuable elements for our society. However the core design elements, when adopted in different places across the world, created what another critic called an “eerie feeling of detachment,” and many of these places are linked with the unease of liminal spaces, alongside the dehumanising effects of brutalist architecture. If only we knew better then, with some modifications, such as inclusion of community and typological diversity, adaptation of ecosystem services and cohabitation with nature, these places would not have become so universally hated.

Just because his exact plan was never built, is not to say Le Corbusier's ideas didn't at least get a proper attempt at working. They were the inspiration for much of the post-war reconstruction housing built in the late 1940's and 1950s in Europe, as well as being the mental grandfather of much social housing around the globe. They were also the basis for what has to be universally agreed as one of the worst designed cities on Earth: Brasilia.

Brasilia: A disaster in concrete

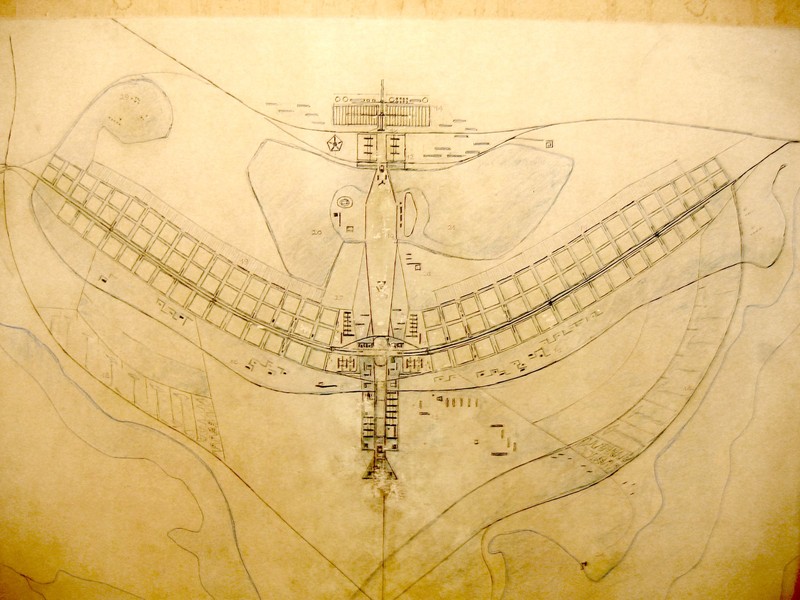

Brasilia Masterplan, Oscar Niemeyer (Uri Rosenheck)

The capital of Brazil was created from scratch to fulfill the political desire to place the centre of power away from the population centres like Rio de Janeiro. It was, from the word go, designed to utilise all the 'best' ideas in urban planning at the time, including those of Le Corbusier. The result was a place that contained some visually stunning architecture to gaze at, but became simply an appalling city to live in. Indeed, from the 1970's until comparatively recently, Brasilia has been the universally designated punching bag for all those who wished to criticize modernist city planning. The chorus of condemnation has been widely repeated, so we only need to summarise the major themes.

Barsilia's center, photo: Arturdiasr

Most obvious, perhaps so obvious it is often overlooked, was that Brasilia was designed to look like a bird from above. Like a gigantic freaking bird. We wish we were kidding. Everything else, all the zoning, all the crucial logistics and infrastructure, even the basics such as street patterns, were all subservient to the idea that the place had to look like a bird.

This resulted in one of the most seemingly inane mistakes one could make, so obvious it shouldn’t need to be said aloud, but guess what? We have to say it; that a city plan is NOT an aesthetic design. It cannot ever be considered as a visual or an aesthetic exercise. It is fundamentally unsuitable to depict any kind of a symbolism to be leveraged as a message. Doing so is a complete recipe for failure, each time it has been done.

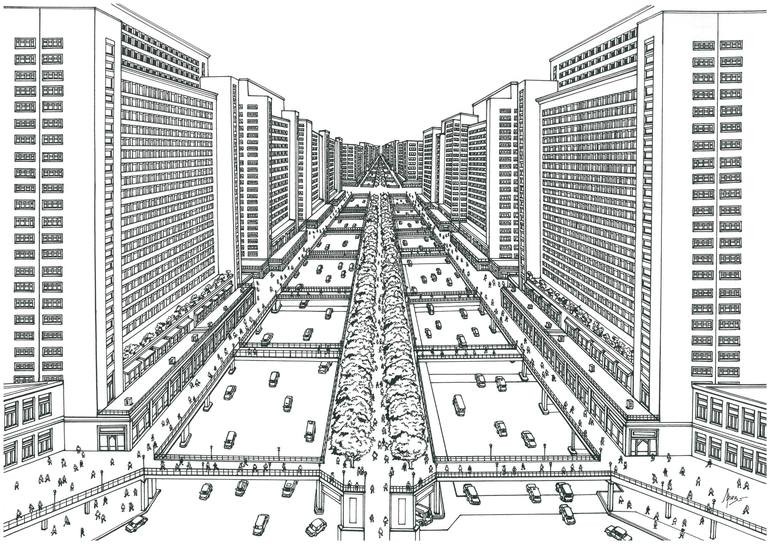

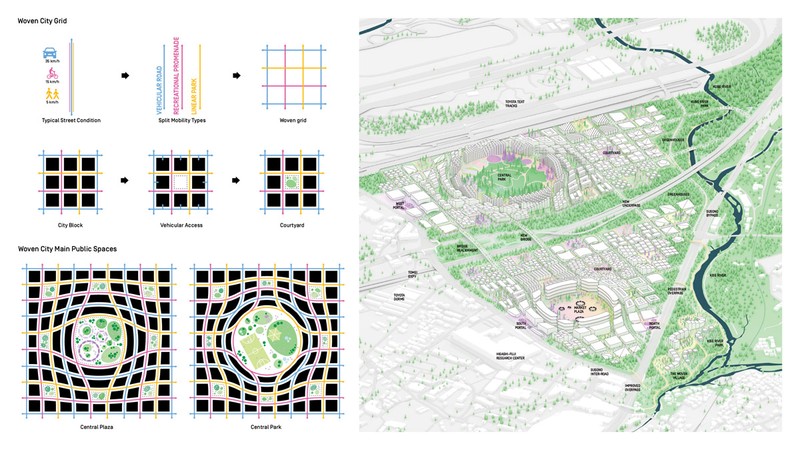

Yet, this still happens., mostly when an architect is asked to design a city. The aesthetic-driven design process of a building leading to follies of the imagination. We can see it repeated in the brand new 'smart city' of Toyota's 'woven city'. Where currently lauded and popularly embraced architect Bjarne Engels has designed a city fabric that literally depicts the logo of the project.

Toyota Woven City plan by Bjarke Ingels Group

Toyota’s Woven City is utterly aesthetic, without proper understanding of the need for cities to be an expression of diversity, and be a framework to grow, develop, and change to be successful rather than an object to design. A neighborhood design like this, where both urban plan and builds are all designed at once, by one architect, goes directly against the necessity for any place that calls itself a city to be from a plural set of voices rather than a uniform visual appearance. Again, an architect sitting on the chair of an urban planner, using some grand aesthetic symbolism as a fabric of a city, repeating the mistakes of the Garden Cities and Brasilia in a baffling display of ignorance. And this under the banner of ‘sustainability’. Thank goodness Toyota’s Woven City is only to be a prototype for testing new technologies, let’s hope it won’t be used as an example for sustainable urban design.

Brasilia's car-centric space is impossible to traverse as a pedestrian

Back to the capital of Brazil. On top of this bird-madness, Brasilia was also entirely planned around the artificial device of the car. Another fatal error. As suburban America has demonstrated overwhelmingly, car-centric neighbourhoods destroy social and economic fabrics of a city, leaving only isolated islands left to their own devices. Here, loneliness, separation, huge energy footprints, infrastructural wastelands and cultural deserts remain.

For its critics, Brasilia failed because its living blocks were cold and antiseptic, and its programmatic separation into vast living areas versus working areas made it depend upon broad and long highways that destroy human scale and caused huge traffic issues. Its plethora of monumental public spaces may have served as iconic symbols of the nation, but were bereft of life as few people visited them, and above all it was condemned for over-planning every aspect of urban life of the residents.

Like the ghost of Fordlandia, Brasilia's design regulated the living conditions from the personal to the professional. All residents, from low-paying office workers to that of the highest government official, were forced to work around design elements set in concrete, leaving little room for the imagination or for individual choice and life. The criticisms hit hard and hit true. And this failure of Brasilia was to have an impact upon later generations as an example of what not to do.

The Sixth Lesson: Utopia cannot have an aesthetic design as a plan. It has to be a framework for diversified development, have the human experience at its heart, including both rich and poor, both young and old, and a multitude of voices. Building on technological devices as central elements of life, such as a car, condemn it to failure.

The trinity of fail: meeting the smart cities

We can see, everywhere, projects built around new buzzwords and ideas, which all suffer from the same folly from the word go- something that looks good on paper but doesn't work as a place to live. How can we spot them in advance?

We should be looking out for core words and terms- like the highly popular buzzword 'smart cities'. Like the terms ‘sustainability’ or ‘ESG investment’, 'smart cities' is one of those wonderful terms that we all kinda know what it means, but don't exactly know precisely what it means. This allows differing people to have differing definitions, work to differing standards and produce differing results (which due to the differing success criteria, they can hold up as a success when it isn't).

Songdo, South Korea. Photo by Gije Cho

Using the term 'smart cities' as a red warning sign allows us to discover, near the top of our list, Songdo in South Korea. For nearly 15 years now, architects, technology experts, engineers and urban planners have worked hard to create a brand new business district for the sprawling city of Incheon, right next to the capital of Seoul, one that would highlight advancements in technology and infrastructure. Songdo was presented as the flagship for how we would live in cities of the future, where technology, big data, sustainability, and smart urban planning would create a modern veritable utopia.

It hasn't gone entirely to plan however.

On paper, Songdo had everything going for it. Incheon, is a large international transportation hub, which would allow Songdo to be easily accessible to both domestic and foreign travellers and potential residents. From its initial planning it was imagined to be completely 'sustainable'. A place that didn't need cars, with less or no pollution, little overcrowding and all extremely high tech.

To accomplish these rather lofty goals, some of the world’s most advanced urban technologies were utilised. The streets that connect the district are lined with sensors that measure energy use and traffic flows. Songdo also features a massive seaside park outfitted with self-sustaining irrigation systems to provide ample public space. At the level of individual residents, trash tubes take garbage away to a central plant where it is automatically sorted into recyclables and waste to be burned. Even the homes are operated by cell phone apps that control everything from heating and air conditioning, to artificial light levels.

Songdo's vast, car-oriented blocks leave humans feel lonely

Many critics and inhabitants alike, however, say that living there is “cold” and “deserted”, with some going so far as to compare it to a ghost town. With a population of just over 80,000, and with the first major phase of development soon coming to an end, it clearly isn't that, but something has certainly gone wrong.

What the designers and planners of Songdo should have done was design around the perspective and needs of a human being first, with technology acting as the supplement, instead of designing for technology, with humans being just in the peripheral. It’s easy to automate many processes, and collect infinite amounts of data- but is it necessary to ensure that a city is performing? Are all aspects of urban performance quantifiable, or can it be described through less tangible measurements like the overall happiness of its residents? Songdo is proof that high-tech cities don’t equate to well functioning communities.

To be fair to the planners, Songdo has a staggering 2 million square metres plus of LEED-certified space within 118 buildings, and averages around a 76% rate of waste recycling. If this wasn't enough the overall energy use per person in Songdo is up to 40% less than in other cities. These are admirable achievements and are to the designers credit. These object-oriented performances do not save the place from systemic failure, though. Songdo, was designed and built upon a technological utopianism, and in that finds its failure.

Songo’s urban environment is packed with highly sophisticated sensors which constantly monitor pollution levels, traffic flows and even citizens’ movements. All this resulted in a frigid living space for many people, and a lack of community. Indeed Pettit and White in their 2018 study of Songdo compared the experience of living there to being in Chernobyl for its sense of emptiness.

Songdo is the poster child for many approaches towards redesigning the urban space; as one commentator said, “designed with extreme efficiency, totally artificial, apparently without poverty or degradation”. Once more, it is the idea that the city can be built like a machine, which leads to imminent failure. Above all it places the human experience as secondary, and is a fixed asset with no attempt to grasp the impact of time upon the city's development. This probably explains why it has failed to draw the big companies it had originally hoped to.

Still, like those Londoner's after their city burned, Songdo is seeing small shoots of rebellion. Rather than big corporations, small start-ups are seeking to utilise Songdo, tiny little human gestures of reclaiming spaces in a way they were never intended to be.

Eko Atlantic City, Nigeria, photo by Edidiong Ikpoto

Songdo isn't alone in presenting the city of the future as a technological utopian paradise; Eko-Atlantic/Smart City Lagos in Nigeria was presented as a six-million m2 waterfront reclamation project. Its aim was to become Africa's core financial centre. Beautiful plans showed us a city of 250,000 inhabitants with an additional 150,000 commuting to and from it daily. Immediately, issues leap out at you; for example- that many people having to commute in and out of a city each and every working day? With no plans for any state of the art mass public transport system and infrastructure to facilitate this? The words ‘disaster of epic proportions’ seem suitable before you even laid the first foundation.

Even if it had no other issues, this would have immediately replicated the problems faced by the city of Boston, whose central financial district is bottle-necked by the fact that not enough people can get in and out of the city each day. They built the 'big dig', a giant infrastructure project to allow for more traffic, one of the largest infrastructure projects ever to be undertaken in the USA, building 161 miles of highway of which half in tunnels, estimated at a total cost of $22 billion (about 12 times as much as originally planned). In short: a practical, financial and technical disaster. Here we learn another important rule for sustainable city design; place destination and origin close together. You should prevent such mass movements of people through programmatic placement. Building more infrastructure simply attracts more traffic, in a never ending spiral of congestion.

Like Levasa in India however, Eko-Atlantic is one of those projects bedevilled by financial secrecy and lack of transparency, and appears to have merely become a gated community for rich people. We shouldn't ignore the fact that the multi-million dollar breakwater developed for the city, proposed to help the community withstand winds and waves from the Atlantic Ocean, has subsequently pushed tidal surges into neighbouring parts of Lagos, which has resulted in deadly floods.

Masdar; The utopian Carbon-free city that wasn't carbon free

Masdar City (artist impression) by Foster & Partners

Songdo and Eko-Atlantic are finally joined by Masdar in the United Arab Emirates to complete a trio of high-tech, well-intentioned smart cities of the future who have utterly failed. Masdar was heralded as the world's first zero-carbon city, with 50,000 residents (and an additional 40,000 commuters), built on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi. Coincidentally, it also cost $22 billion to build. Much thought went into creating this sustainable city, supposedly to be powered entirely by renewable energy sources. Grand dreams were dreamt of state of the art water recycling systems, insulated buildings (using argon of all things), electric automated driverless cars, and a gigantic wind tower that would suck cool air from above and pump it down to provide natural air conditioning in the streets below.

Headlines of failing Masdar litter the internet, this one from Inhabitat

Even in the planning stages, you could see critical failures and flaws being built into the project. The most important one is that it was also master planned by an architect (in this case Norman Foster) and fashioned from an aesthetic perspective. Looking at any of the pictures of Masdar, you can immediately see the heavy handed aesthetic that dominates its urban shape. Again, a singular, mono-cultural, aesthetic design, like a machine to live in. Designing the city like it is a building or a machine, once more, doomed to failure.

Masdar Ghost City; from Failed Experiment in Sustainable Planning

Several of these design elements are in place. It's just that, simply, no one wants to live there. Added to this, the designers have admitted they cannot actually deliver a zero-carbon city with technology alone. Fighting against nature, once more, the technical dream fails in the face of ecology, with the sandstorms and heat winning over frail human technology. Masdar, today then, is a shell, with less than 10% of the city completed, its office buildings standing mostly empty. As one writer put it, “Masdar is, essentially, the world's most sustainable ghost town.”. Here, we see that in Masdar we can detect several of the previous lessons combined: a single-vision architectural aesthetic design as a master plan, a fundamental reliance on technology to provide basic living needs, and a limited diversity proposition for its demographics ending up in a fundamental failure of city design.

The Santander Experiment

All of this is not to say that integrating technology into new cities is a bad idea per se, it is that integrating them into the core of their planning is, as smart cities invariably try to do. There have been some experiments in urban planning with technology that have highlighted the underlying issues technology presents perfectly.

Here, a good example is the Spanish city of Santander on the Northern coast. Santander is an old mediaeval city that grew organically, and is a lovely place for most of it. The intervention here is the installation of 20,000 fixed and mobile sensors throughout the city. You find them everywhere; they are attached to buses, placed in parks, inside public buildings, they even attach them to the waste bins. These sensors capture everything, and their data is then able to inform passengers at bus stops the exact time their next bus will arrive, inform park workers when the best time to water the plants is; when to dim lights when there is no one on the street at night, and even when cars or pedestrians are coming by so they can be turned back on.

All these sensors create huge volumes of information, creating a gigantic matrix of data, which facilitates the aggregation, analysis and visualisation of these particulars, which then, in turn, promises to provide invaluable tools for city leaders, business, developers and the citizens themselves.

Crucially Santander didn't just seek to focus on the technology alone. It was just as concerned about how citizens would respond to the collection of this data. It asks if the cities/nations/the EU's legal and regulatory environment was compatible with the project? It was designed to investigate what business model would be needed for the ongoing project to be financially viable after its initial pilot phase, which was heavily dependent upon funding from external sources such as the EU.

If anything it is these questions that provide a focus to the Santander experiment and all such projects that depend upon the collection of huge quantities of metadata. Santander is proof of concept that such ideas can work, especially as things like the costs of installing the sensors dropped with greater adoption of the devices, but that serious ethical and financial issues hang over all such grand ideas. These problems are amplified when facing privately funded similar projects, such the oft controversial Google Labs/Sidewalk experiment in Toronto, which failed due to lack of support of community stakeholders, and was cancelled finally in 2020.

But even these questions ignore the most fundamental one- at what point do we NOT need technology to solve a problem? Given the global state of municipal finances, is high end, high cost technology with the vast expense of installation really going to be a cost saver? And do we need sensors to tell us when a waste bin is full, when just arranging regular collections could work just as well?

The true strength of the Santander experiment is that the technology augments a working, human city. Turn off all the sensors, and the city continues to function just fine, as do most cities grown from mediaeval foundations in Europe. It is a redundant 'extra', intended to polish, finetune, provide insight and knowledge. It works in Santander, because it is not the foundation of the city, and is not a vital system for its continued success. This is the main reason why such a project works well, as opposed to making technology the essential foundation on which the city has to rely to function, like in Masdar, or as in the next project, Neom’s the Line.

The Seventh Lesson: Technology is a powerful tool in helping us operate cities of the future, but unless steps are taken to treat it only as an additional tool, and not be its foundation, it becomes a recipe for failure.

NEOM The Line: The largest failure yet to happen

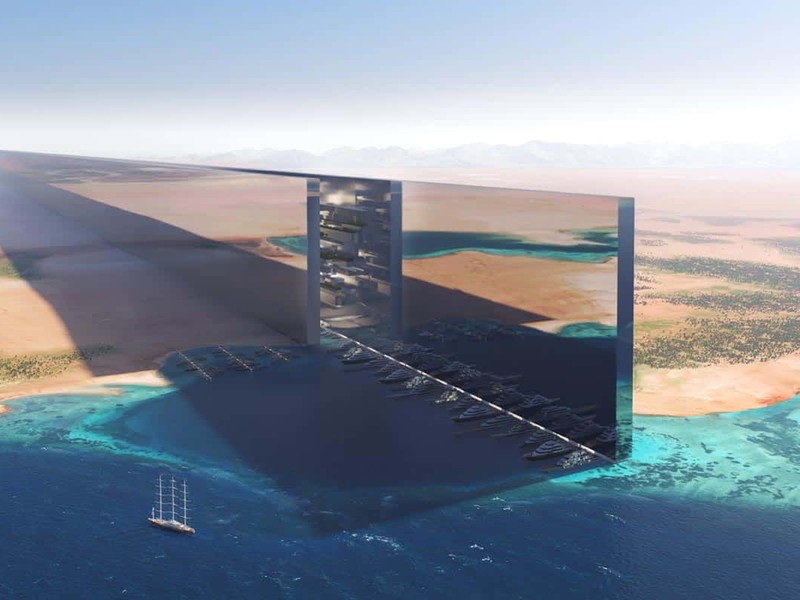

Photo: NEOM

It is now we encounter arguably the most important 'city of the future' of modern times; Saudi Arabia's ambitious and utopian NEOM project. NEOM is an area the size of a small country in the northern western Arabian peninsula, containing various projects, including the utopian city called ‘The Line’. This is one of the last and most ambitious probably-will-end-up-costing-a-trillion-dollars plans to construct the city of the future. The project has been critiqued already, by many, all seemingly before it really started, and it would need a good decade before we can assess if NEOM’s projects are destined to be a true technological/urban utopia, or just another white elephant in the graveyard of such things. However, looking at the above lessons, there’s quite a few things worth predicting about it.

Photo: NEOM

The early signs are the opposite of good. The current incarnation of NEOM’s projects are exceedingly difficult to build, and even if successfully built, would create what is by every sane metric a dystopian nightmare whose only contribution to the world will be the inevitable betting pools profiting from predicting when the entire thing falls apart or not.

Photo: NEOM

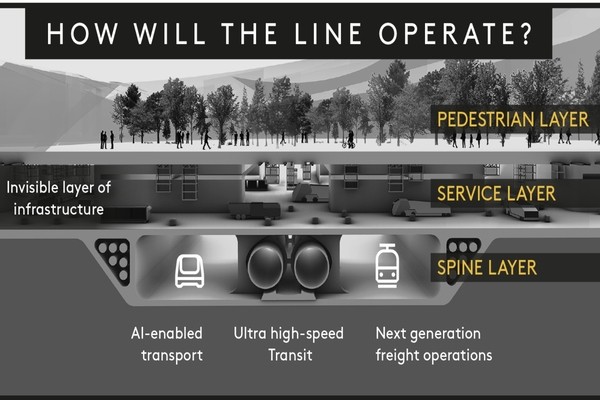

Its issues begin with The Line- the wonderfully rendered CGI hellscape of city that will make up the main body of the project; this is supposed to be a 170 kilometre long city, 500 metre tall, and 200 metre wide. Cutting a swathe through the Arabian desert, straight through mountain ranges, before being encased entirely in mirrored glass from all sides. To put this into context, 170 kilometres is about the distance between the Dutch capital city Amsterdam and the Belgian capital of Brussels. The Line’s 500 metres in height is a comfy 10 stories higher than the Empire state building, from bottom to tip.

Starting off, its social record isn’t off to a good start. To cut the city through the landscape like this, indigenous people are displaced, and several people have been sentenced to death for resisting this displacement. Oops, there goes one leg of the three legged stool of sustainability.

Online advertisements claim that residents will always be within five minutes of amenities and only two minutes away from “nature”. Life is enabled with the promise of technology, of a ‘cognitive city’ that can adapt to the needs of the citizens, and even preempt them. Read differently, this is a polite way of saying you will live under constant surveillance, not just by cameras, but by a score of monitors all of which will insist no doubt that your smartphone ties into them. Like Santander, but designed by George Orwell.

Technology here is not just embedded in the foundations of the city, it makes up the entirety of its operational paradigm. You may as well live in a colony on Mars with Elon Musk controlling it through tweets.

In transportation alone, The Line is a horrendous nightmare just waiting to happen. Apparently the entire massive 170km long construction will be served by one high speed train line, one local metro system, and one freight train line transport method, all built into the foundational basement level of the city. Room for expansion of this later? Zero. So for the city to work at a basic level, it will need these lines built while the building is being constructed. So as well as a 170 km long, 500m tall skyscraper, they are also supposedly building 340km of train tracks to run underneath it, alongside the vast water/waste/electricity infrastructure.

That high speed link is supposed to be able to get people from one end of the city to the other in 20 minutes, which means it will have to run at about 510 kmph (faster if it has to stop to let passengers on and off along the way, as you know, you kinda would like to visit grandma).

Photo: NEOM

If one element fails in this whole scenario, then the millions of people who would depend upon it to get to work, hospitals, or grandma, are now late. Whole sections of the city would be unable to travel anything but short distances if there were required maintenance closures or overhauls needed, and if there is a delay on the freight line, then crucial food supplies will stop. From a resilience perspective, it’s about the worst way you could conceive of city infrastructure. You could not design a more un-resilient city if you set your mind to it. So that’s the second leg of the sustainability trifecta eliminated.

The shops that are supposedly only 500 metres from your cognitive habitation pod will need constant deliveries, otherwise you and your neighbours are going to be in trouble really fast, embedding a gruesome energy footprint into the basic habitation patterns alone.

Promotional artist impression of what it is suggested it might be like inside NEOM the Line. Photo: NEOM

Air Taxis have been suggested as another possible travel alternative, because what could possibly go wrong by having helicopters working within an enclosed urban area? Unless of course they only fly outside, along the top of the skyscraper, which means areas created to allow light to the poor denizens of the dark reaches down below will find the supposed rooftop access restricted, and being realistic, being restricted by a method of transport which only the rich can afford.

The Line can only work with a fixed population of between 4 and 9 million people. It cannot cope with numbers larger than 9 million and anything below 4 million means large areas of the city will be unused and redundant. It will become like Masdar; only a version of Masdar where they can’t close down sections as the entire thing needs all sections to be working.

Populations will be forced to live on top of one another, creating in effect Kowloon Lite; while we can hope the designers have thought out how to prevent living at the bottom levels becoming a Blade Runner-esque twilight, one imagines that travel to the top will have to be facilitated by lifts and escalators. The Empire State building needs 73 elevators in order to move people around it. Even saying The Line will require just half that, we are still talking of a building that will require about 15,000 elevators at the very least, with the power requirements and issues that come with it. These are hard infrastructural needs in such a configuration. God forbid something goes wrong.

Resources will have to be spread along the entire length; it is supposedly going to be powered by renewable energy. In order to do that, it has to power not just the 9 million people living in a desert community, but also the incessant cooling requirements, all people, water and food transport, and all this necessary infrastructure needs to be in place, always, without fail. Again, like a colony on Mars, requiring near space-agency precision and redundancy on its technological operations. Which it can’t have on its aesthetic-driven footprint design.

These observations are just obvious considerations that can be leveraged instantly, without even looking at the absurdity of its ultra expensive mountain resorts or the mad idea to build a sea port with half the urban areas being constructed on the sea itself, when there is literally no shortage of land around it. Ironically the seaport city is shaped like and named “the Octagon”, perhaps as a wink to precious utopian and never realised city designs?

NEOM's Octagon City - Credit: neom.com

NEOM begins by seemingly breaking every one of the rules of building Utopia. It is fundamentally aesthetic in nature, the design architect sitting on the chair of the planner, it is fundamentally enslaved to technology, it negates every single rule of nature and ecological integration, and it is fundamentally anti-human in scale. And that’s before it even starts.

The prognosis isn’t bad- it’s horrific. As Adam Greenfield in Dezeen Magazine puts it "All those complicit in Neom's design and construction are already destroyers of worlds".

And yet, while we could spend hours more getting into detailed critiques as to why NEOM the Line represents the worst of all possible plans for a city of the future, the plans themselves highlight a larger issue. One that all the other failed utopias described above all seem to tie into, the failure of addressing utopian city design as a progressive expertise that learns from the past, and applies these lessons to move forward towards the future. Why does NEOM gather so much funding, and subsequently, how is it possible for such a project to come so far, before someone says: “this is madness, a waste of resources, and from that standpoint alone, fundamentally unethical”? As we live in the age where a single picture and 280 character tweets can determine the fate of projects, there seems little respect for the need of foundational understanding of cities, before they are planned and slapped down like sketches in the sand by a toddler.

So while mocking the fallacies of The Line project or the even bigger issues presented by NEOM, they do come across as merely indicative of deeper issues within the context of designing cities able to cope with the massive increase in urbanisation taking place globally.

Planning and building a city of the future then, has been, it seems, an exercise in lost causes, good intentions and utter failures. A key issue that keeps repeating itself is the desire for people to place lofty visualised object-oriented plans as the only possible solution to our problems. And by that measure, it is the rejection of the holistic approach that leads to these failures. The holistic approach requires subtle insight, layers, and non-visual structures to apply. It requires a collaboration between many disciplines, and designs adapted to context, free to change in time through its community. These things seem a bridge too far by those commissioning city designs, and simply fails in the face of the next fancy shaped lighthouse project by some starchitect that thinks they can sit on the chair of God and design a working Utopia. Because of course they will not fail where all others did.

It is the responsibility of both those in public policy that create the processes that lead to the commissioning of city designs, as well as the designers themselves that need to shine a light onto reality. Any city design is inherently a design for utopia. And every design for every neighbourhood, everywhere, deserves the attention and care to apply a holistic systemic approach to determine not just its starting position, but also about how it will develop in time.

Time’s Arrow

Photo: Paolo Bertolini

Time is what really tears up the traditional ways of designing cities. The failure to take on board what it actually means. What an area is designed to be originally, isn't automatically going to be what it becomes. Look to Songdo- spaces that were supposedly designed for large corporations are now being sought by small, bespoke start ups, and that's within just 20 years. Picture this on a scale unimaginable, and you are close to understanding the needs of an actual city.

Look to London again as another example. Near the southern bank of the river Thames, scores of long warehouses were constructed to provide the facilities to allow the goods that arrived at the nearby docks of what was the heart of the world's largest mercantile power, be offloaded, stored and moved on. Millions of tonnes of goods were brought in, and placed in carefully designed spaces, often with built in working cranes, a veritable nexus of industrial and commercial activity.

Time happens. The world changes. The Empire fades, the trade begins to slow. The nearby docks get less custom, less goods get exported/imported. The warehouses begin to stand empty or fall into disrepair. Warfare happens and much of the area is damaged. In time the vast buildings become icons of a lost era, utterly unsuited to where they were. What good at this point would it be to insist that this region is designated 'commercial/industrial use only' when the commerce has fled? What use is structural segregation at this moment?

See these self-same buildings today. Refashioned to become homes and flats. Many retained their original external features (including the cranes and loading platforms). They exist as part of a working community, showing flexibility and adjustment over a century in time.

Photo: Nicolas Vollmer

Considering time as a basic element to be included from the very beginning also aids in coping with another blind spot in many plans for the next generation of cities. There are always plans to facilitate growth and expansion, but one rarely sees anyone include plans for what happens when the city shrinks, when de-urbanisation occurs.

How do we plan the loss of taxation as populations decrease, or how to deal with the urban blight that happens when people leave an area? As one Professor Pardo pointed out, “On average, a single blighted property can cost a municipality tens of thousands per year in direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include code violation enforcement and engineering and property maintenance. Indirect costs include uncollected taxes, devaluation of adjacent properties and impact on city services such as police and fire calls. Increasingly, studies of urban blight are looking at the impact of blight on other social and economic issues, such as public health and economic opportunity.”

We are drawn to the example served to us by the Japanese town of Kosaka. Once a much more vibrant place, the rural town has seen its population drop to a mere 5,000. In the past, the town supported 3 separate schools, teaching a range of students from kindergarten up to High School level. As Kosaka experienced the population losses much of Japan has faced, with the turning of the years, the numbers of schools aged students dropped, until they closed two of them, utilising just the one building to cover all the town's educational needs.

This then presented Kosaka with the dilemma of two large, well built, and functional school buildings that were standing empty. The solution was elegant, pragmatic and simple. They took one and made it the town hall and regional administrator centre. Rather than waste money building a new structure, they simply repurposed one of the old buildings (which currently means they have more than enough space for all their civic needs and with an entire floor of the building they can expand into if the need arises). Then the other building they gave to an NGO to teach foreign students Japanese. Kosaka is a lovely example of how you can adjust to population loss positively and plan for your own future.

The Eighth Lesson: Utopia needs to be designed with time and the impact of time considered from the word go; a failure to understand that even cities have natural rhythms of growth, expansion and contraction, is a failure to understand urban spaces at all.

Professional Taxidermist's need not apply...

The issues, the context, of all aspects of urban design and planning, not just of new cities of the future, but of our existing cities as well, is that we need, desperately need, holistic approaches to work alongside reductionist solutions. The easiest way to do this is to not make the opening and cardinal mistake of starting to plan for a city with an architect's drawing.

As Jane Jacobs wrote in Death and Life of American Cities, “To approach a city, or even a city neighbourhood, as if it were a larger architectural problem, capable of being given order by converting it into a disciplined work of art, is to make the mistake of attempting to substitute art for life. The results of such profound confusion between art and life are neither art nor life. They are taxidermy.”

The Rules of Building Utopia

Image: "Google's parent company wants to build Utopia" - Vanity Fair

We have covered a lot of territory here. In many ways this is because we decided we didn't want to cut corners and produce a shorter, more simplified, version of our thoughts. Simplification, while a required attribute in a world with limited time and limited attention spans, can also lead to maladaptation.

In looking at so many examples of previous attempts to create Utopias, communities fit for purpose in the changing world to come, we have tried to demonstrate the hard lessons learned by others, played out over centuries in the score of examples above.

Each lesson we have highlighted has been born out of those earlier attempts and while not strong enough to empower us with hindsight, they do stand as things we must keep in mind as we strive to create new places to live in.

As we seek to design the communities of the future, we have to keep in mind what the above examples teach us. That our plans for future communities must be grounded in the pragmatic; a dream city cannot depend upon wild speculative ideas and unproven technologies. As a caveat to this, to accept that while we as humans need to cling to religious or political or even holistic belief systems, no belief system exists that can grasp or encapsulate the complexity of cities, which require a large measure of pragmatism that causes many projects born out of such ideologies to fail.