On the evening of the 13th of November 2021, Alok Sharma, the acting president for COP26, the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference, proudly declared that history had been made in Glasgow. However, his closing words, spoken a day later than the conference's intended end, were an emotional apology that seemingly defied this positivity.

The tense two-week meeting ended somewhat confusingly, leaving many of us wondering - what were the event's actual outcomes? What does the Glasgow Agreement mean for the future and our current climate crisis?

Firstly, let me break the unfortunate news - COP26 didn't achieve as much as many had hoped. However, it wasn't all bad either. This article provides a brief rundown of the event's highlights and ends with a review of what it means for Orchid City.

Finally Discussing Fossil Fuels

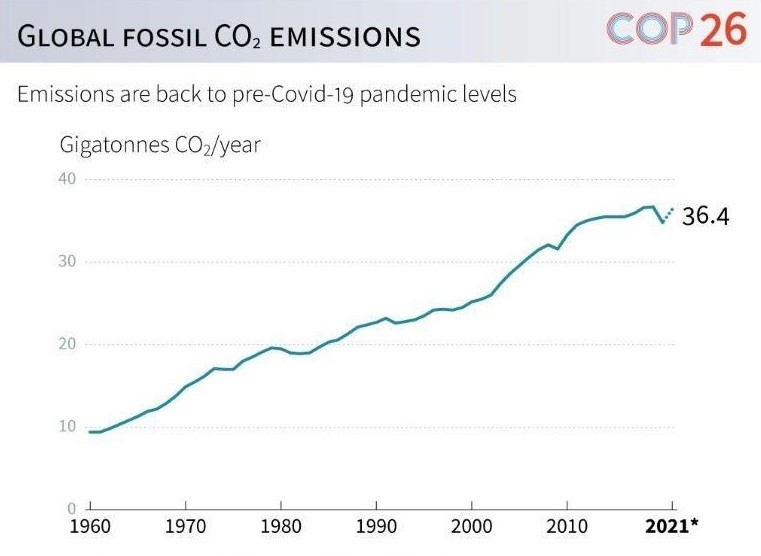

It's hard to imagine, but no UN climate summit in the last 20 years has drawn the direct line between fossil fuel use and its relation to rising emissions and atmospheric temperatures. This willful blindness was primarily due to the fierce opposition from nations dependent on oil and coal consumption.

However, its inclusion in 2021 shows that attitudes are finally changing. The widespread recognition and acceptance that reducing fossil fuels as the most effective mitigation tool is excellent news. When it comes to implementing and enforcing this philosophy, it's a very different story.

Most members came to the meeting hoping to keep the limit of a rise in global temperatures to 1.5C, the agreed figure at Paris in 2015. Throughout the conference, representatives of 196 countries compromised and eventually agreed to reduce their emissions to keep this target.

Unfortunately, that deal fell apart in the final minutes of the last day - which had already been a 24-hour extension to the original fortnight planned for the program.

Controversial Coal Disagreement

As they penned the final draft, India, China, and South Africa, some of the world's largest polluters, raised concerns with the exact wording around coal-fired power generation.

India led the objection, proposing to rephrase the statement. Instead of using the term "phase out" the use of unabated coal and subsidies, the agreement should actually say "phase down".

Controversy ensued. Several delegates from Europe and the Pacific regions voiced their concerns and criticisms. After all the sacrifices they had been willing to make, the world's largest polluters spoke up when the time was short and backtracked on what they had promised in the days before. Many nations felt disrespected and somewhat cheated by this move.

As the curtains began closing on the event, their impassioned statements weren't enough to change the outcome. Sadly, this disagreement on coal use and the way it played out define the COP26 climate conference.

Alok Sharma accepted the changes but made it clear he wasn't entirely happy about it. Hence, offering his apologies to the entire conference for retracting and overriding what they had already agreed upon.

These watered-down commitments have meant the targeted warming temperature has risen from 1.5C to a recalculated 2.4C. This increase will be catastrophic and won't prevent a rise in global temperatures from going beyond a safe limit.

COP 26 has gone backward on what was agreed to in Paris 2015 - things are becoming much more urgent.

Shortened Timelines for Negotiations

Thankfully, there was some good news.

Each country has its own nationally determined contributions (NDC) plan to cut emissions by 2030, which, under the 2015 Paris Agreement, were to be reviewed every five years. COP26 declared that NDCs are now annually negotiable.

This reduced timeframe (in theory) will allow countries to reset agendas easily and, more importantly, become more tuned to the idea of changing and evolving to situations as they arise. Considering the time frame and urgency to address climate change, the ability to regularly reflect and revise our goals is crucial.

At next year's COP conference in Egypt, every country attending will be back at the negotiating table, as they will be every subsequent year. Skeptics (there are many) are unsure whether this will make any long-term difference to actual outcomes.

If they couldn't make a deal and stick to old targets this year, who says that 2022 and beyond will be any different?

At least it offers a little more hope that our leaders will be forced into becoming more adaptable. There's also a possibility that we will see better acceptance of innovation and more valuable transformations. Unfortunately, that's a lot of uncertainty for a governance system that isn’t showing it is capable of adapting fast enough to the needs of the present, or the future.

Time is running out - we need more actionable change and policy is letting us down.

Financing the Global South

In 2009 an agreement was made that the world's wealthier countries would financially help the developing countries, promising over US$100bn over the next decade to help cut emissions and reduce the impacts of climate change. They didn't meet their promise, coming in well under that figure, and developing countries feel let down.

The agreements that came out of COP26 haven't promised an exact figure but a pledge to deliver more, potentially US$500bn over the next five years, to the global south and poorer nations.

However, this time leaders agree that more money must be spent towards adaptation infrastructure, rather than emission reductions, as it’s much easier to monetize the latter. Discussions on "losses and damages" and the possibility of repatriations to countries that have suffered severe losses due to recent disasters fell apart at COP26. Next year will see these talks resume.

While the developed world historically is responsible for more than 79% of all CO2 emitted1, the developing world is now the largest current emitter, with over 63%, and China consisting of a large chunk of that2.

With the developing world carrying much of the weight of implementing change, while also struggling with some of the largest consequences of climate change, it is good to see a doubling down on the commitment for increased funding. But here too, simply continuing and trying to increase the change-path is unlikely to be fast enough to curb the emissions to stay under 1.5C.

Summary of Outcomes

Not many new or positive actions emerged out of COP26. Many experts claim that the meeting has made no progress on the 2015 Paris agreement and has gone backward. As it stands, the prior commitments we had made to keep warming under 1.5C is near impossible.

Despite whatever good intentions these types of conferences and the delegates who attend them may have, they continue to solidify to us the fundamental lesson that studying societal system dynamics teaches us. This is that complex systems have a strong historic inertia, and that big changes from evolutionary adaptation through policy measures has never succeeded.

Therefore, we desperately need new avenues to accelerate the way we change. And policy, as important as it is, isn’t providing that answer.

How Orchid City Matters

The fact is, it’s going to take a wide range of different methods to create the acceleration we need to address the climate crisis. Furthermore, a global policy can only demand specific actions when already-proven methods exist and show how to achieve them. We conceived Orchid City to address this problem.

The built environment, and our interactions with it, is the most significant driver of climate change by far. The construction sector alone is responsible for more than 39% of the world’s carbon emissions. In addition, how we design and build our cities today will have a significant impact on the future sustainability of our cities, particularly with transportation, agriculture, and industrial production.

The incremental improvements of our current pathways are not getting us to where we need fast enough. To generate large enough positive change, we need to have new and tangible brick-and-mortar examples of systemic, fundamental change. Today’s future-oriented city designs, such as Masdar, NEOM, and Toyota’s Woven city, focus too heavily on emerging technology for solutions and fail to do this. They provide few answers on how humans can live affordably, in harmony with our environment and within our planetary boundaries.

We have yet to see any physical examples that demonstrate and produce such long-term, globally-minded, and systemic societal changes. Orchid City’s mission is to be the pioneer, and prove that it is both financially and technologically feasible.

By offering a 140% per capita reduction in carbon emissions, Orchid City pulls the future of living twenty years forward into today. Still, emissions are not the only challenge - most of the UN’s 2030 sustainable development goals (SDGs) are connected, and can be addressed within the same built and lived environment.

For example, the Orchid City concept fosters energy self-sufficiency, together with efficient organic agriculture and closed-loop water systems. At the same time, Orchid City’s affordable housing and accessible education drive actions toward the SDGs of poverty, inclusion, equity - all vital to ensuring a thriving and affordable community. In terms of sustainability, nothing should be seen in isolation nor devoid of humanity.

Recent developments with the Orchid City model and new partnerships in Africa show that it may also be adjusted to suit the context of developing countries. This can help provide similar pathways for countries in need of radical systemic change - developments such as Orchid City can provide the vessel for these to gain a foothold and scale-up.

If COP26 has shown us anything, it’s that a clear vision and concrete systemic solutions are more critical now than ever. Concepts like Orchid City can help manifest alternatives to tackling climate change, proving that a sustainable future is possible. This way, we may realize the change on the ground we need to eventually influence policy and remain below that all-important 1.5C limit.

24 november 2021