Salesforce Park and Transit Center in San Francisco is a one-of-a-kind transport and recreation complex located in one of America's most exciting cities. The jewel of this crown is Salesforce Park. This vast 2.2 hectare green space on the 8th floor of a transit center showcases how inner city concrete jungles can be transformed to vibrant urban parks, fully integrated within a city, provide ecological benefits, and nature-filled community spaces.

Except researched and created the concept for what became the largest ecosystem rooftop in the world for the client, architecture office Pelli Clarke & Partners. Today, Salesforce Park and Transit Center stands as a global example on how we can change the way we can transition city biodiversity, health, and sustainability.

Global competition, localized design

The redevelopment of the Transbay Transit Center (the name prior to and during construction) was put to tender through a global competition. At the time, it was one of the largest architectural competitions ever held. On September 20th, 2007 the TJPA competition panel announced that our rooftop park concept had won, together with Pelli Clarke & Partners' design for what is today's Salesforce tower building adjacent to the transit terminal and park.

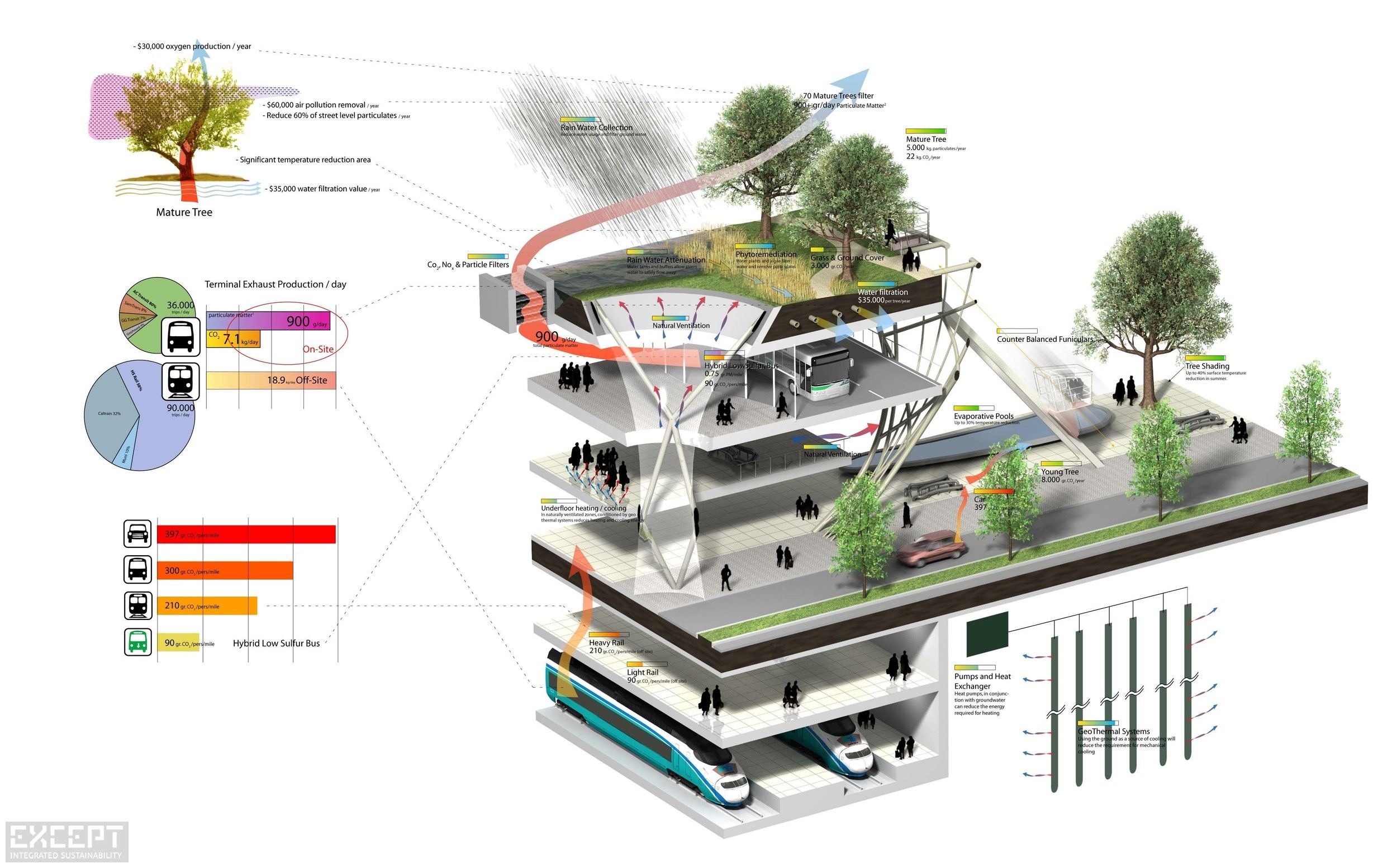

Our research into the area showed this are in San Francisco's downtown to be heavily concreted and asphalted over. It was in dire need for ways to cool down the ever increasing heat island effect, promote much needed biodiversity, provide climate-adaptive response to increasing rainfall, and provide a vital place for people to connect and socialize outdoors. Based on this, we built a concept that utilizes ecosystem services to do tjust this: cool down the area, capture and store rainwater, boost ecosystem quality and biosiversity, as well as provide spatial quality, health benefits, and economic value to their immediate neighborhood and beyond.

The park is 5.4 acres (2.2 hectares) in size and currently caters to approximately 1.1 million residents who live within half a mile radius, as well as hundreds of thousands of annual visitors from outside this area.

Salesforce San Francisco Transbay Center, as it is now known, features innovations such as water and air purification, ecosystem services, and biodiversity boosters to provide a cleaner environment and welcome flora and fauna back into the city. These features are key to contemporary and sustainable urban renewal. The local landscape design office PWP Architecture was responsible for the detailed design of the park.

Transbay Terminal: the case for renewal

The original Transbay Terminal was opened in 1939 to serve the city as a train station. It was converted into a bus depot in 1959 after struggling to expand the network and failing to sustain financial viability. Over the following decades, it thrived as a bus terminal, mainly serving San Francisco's downtown area and communities of the Bay Area.

The Transbay Terminal diversified its use over the years with the bus terminal housing a diner, a cocktail lounge, a newsstand, and a police station. The center adapted over the years but always struggled with a longer-term vision. In the 90s, earthquake damage and new safety regulations forced all tenants out and most of the center remained dormant.

In 1999, it was officially announced that the damaged terminal was to be replaced. After more than 70 years of operations, the original Transbay Terminal was officially discontinued as a bus terminal in 2010 before being demolished.

Salesforce Park: the jewel in the crown

The terminal's redevelopment aimed to create a unique and functional replacement for the old transportation hub and create an icon that brought people together for recreation and community development. The new center comprises underground train stations (not yet operational), a bus terminal, and retail space. However, the rooftop park is arguably the highlight for most users.

The park sits atop the 1.5 million square foot Salesforce Transit Center. It comprises walking trails, a "bus fountain" that follows the coaches' travel on the ground floor, a playground, an 800-person amphitheater, and a restaurant. It also has an extensive public square and quiet areas set aside for reflection.

Considering the scope of this project, the environmental concerns were considerable. With Atelier Ten, our ecological engineering partner, the Salesforce Park design culminated in a globally unique proposition. Except was involved in core concept generation and roof park development, including the environmental system, water features, air purification, and funiculars/gondolas. Likewise, we also helped produce the main square, bridge connections, and conceptual park landscape design.

Aside from its ecological purpose and visual beauty, the park is designed for mixed uses and as a sustainability-focused community hub for fitness, performances, education, and cultural engagement. There are 15 entry points to the fully-accessible public park, connected by footbridges to nearby buildings such as Salesforce Tower and 181 Fremont.

Ecological and innovative urban design

The park at Salesforce Transit Center is unique, not just in size and locality but in regards to the features and functionality of its ecosystem-driven design. It's much more than just a rooftop with a few pot plants. Dotted about are some 600 mature trees and 16,000 plants across 13 distinct botanic areas such as redwood groves, desert and Mediterranean gardens, and a swamp/wetland.

Some of the more unique features that enhance the functioning of Salesforce Park's ecosystem:

- integrated deep-soil ecosystems with mature trees

- biodiverse self-managed ecosystems

- rain and storm water collection from surrounding buildings

- water buffers and retention methods to save water loss and relieve city infrastructure

- rainwater filtered through the ponds and reed beds

- air from the bus terminal is extracted and purified by filters in the soil

- energy system utilizing ground-coupled heat storage for significant energy savings

Neighborhood revival and profit sharing

Except proposed an innovative profit-sharing scheme to help fund the park, encourage cooperation and actively involve nearby residents and developers with the complex.

First, properties surrounding the park were valued by an independent and well-established third party and compared to future values - projected to five years after its completion.

Such a redevelopment and feature in any part of a city, regardless of the exact locality, undoubtedly adds significant value to nearby properties.

Developers struck a deal with owners to share a certain percentage of this rise in property value. However, the project share was relatively small, and the property owners would gain most of the profits. Despite the low percentage given to the project, it provided enough support capital to ensure the park could remain public and enjoyed by all.

This collaborative profit-sharing initiative is easily replicable and a prime example of how circular business models can fund public spaces and sustainable urban development.

Current operational state and future plans

- In 2017 the project was renamed Salesforce Park in a long-term sponsorship agreement with the Salesforce company, including the nearby Salesforce Tower.

- Bus services began operating from Salesforce Transit Center in 2017

- Salesforce park officially opened in 2019

- The underground train terminal is estimated to be completed by 2030, connecting the Transbay Terminal to the local commuter network and proposed high-speed rail link to Los Angeles.

June 1, 2006