Merredin Health Industries Spirulina Plant

Rural Regeneration Algae plant

Jun 10, 2001

The Merredin Spirulina plant is one of the first projects we applied systems thinking and our holistic, systemic approach to innovation, using ecology as the core driver. The concept, developed in 2000, outlines the case for a spirulina algae plant and a highly unusual but stunningly effective approach for a sustainable environmentally-based industry to revive Merredin, a small desert town in Western Australia. This project is a testament to the strength of studying systemic dynamics and the approaches that evolve from the process. We documented the project extensively, including the conception process, business case, and plant design.

Merredin is a small town in a semi-arid region of Western Australia, about 3 hours east of Perth. It has a population of approximately 5000 residents but unfortunately is plagued with several problems, most critically, rising levels of saline groundwater, economic decline, and a host of associated social issues.

After extensive research into the local conditions and economic possibilities, we developed a solution to help address some of the problems Merredin was facing. Most importantly, it would address and bolster the town's sustainability.

Spirulina is known for its many health benefits and high levels of protein, vitamins, and minerals. Considering the environmental conditions in the area, we deemed it to be the most viable and resource-efficient project for the town of Merredin.

The project centered around a historical pump station. Built in 1903, it was near the point of collapse and in dire need of restoration. This situation offered a great entry point for us to renew the pump station complex and include a restaurant and health facilities, supporting a beautiful and fully sustainable source of income for its inhabitants and a brighter outlook for the town's future.

The existing measures for resolving the town's problems were inadequate.

Industries and businesses were leaving the town, leaving it stripped of jobs, resources, and motivation. With such a complex network of interrelated issues, we used SiD's systems analysis method to unravel the issues and find holistic and fundamental solutions to the town's problems - and it worked.

We mapped the physical parameters of the area, including climate, land use, available resources such as waste and natural sources. The social situation was charted as well, including the availability of labor, skillsets, demography, culture, and the dreams and desires of the individuals living in town (including children).

Lastly, the ecological and economical flows were mapped to round off the system analysis.

We subsequently sought to connect available but unused resources to the desires and demands of the town. By cross-pollinating these needs and resources we found a myriad of possible solutions. We then narrowed them down to the most promising.

One solution, while unusual and unexpected, popped out as a high potency solution to reconnect all these issues in a long-term and economically strong manner. It came out of our research into using ecology as a driver of added value. The result was the possibility of a specific algae type to grow in the saline groundwater of the region.

This ecological solution, coupled with the solidity of the health foods industry fitted perfectly within the existing framework and capabilities of the town.

A spirulina plant was chosen for several reasons. Most notably, its suitability to the climate, ability to solve multiple problems at once, and economic strength.

Spirulina has been cultivated successfully for quite some time and used for a myriad of applications. The main goal of the Merredin plant is for consumption as it yields the highest profit.

The market for spirulina is substantial and continues to grow. It has a high value, and consumers' willingness to pay this price makes it an excellent industry for economically depressed areas. There are several examples of South African towns using algae plants to revitalize their economies successfully.

Spirulina farming is a highly profitable and very ecologically friendly enterprise. The manufacturing process requires very few additives, is relatively straightforward, and Merredin's location on the main highway stretching between Perth and Sydney is a bonus.

An economic and business case was drawn up. It quickly showed us that it would be economically feasible, provide plenty of jobs to locals, and easily mesh with existing infrastructure, only using abundant resources in Merredin.

The plant would return on its investment within five years of operation with a large margin for error in planning.

Merredin lies in a shallow arid valley stretching over dozens of miles has low rainfall and a consistently high groundwater level. Whatever water is available is highly saline, causing problems for locals with persistent cracking in the foundations of buildings and roads. Despite these challenges, the underground water is relatively abundant. A reliable resource base is possible if extraction is regulated correctly.

The plan with the spirulina plant is to ensure any excessive groundwater use (and associated runoff) is caught and redirected by agricultural drains under the town. From there, it is sent via an existing creek and processed by solar desalinators - a vital step in slightly reducing the salinity. After this stage, the water can be used as a growth agent for the algae.

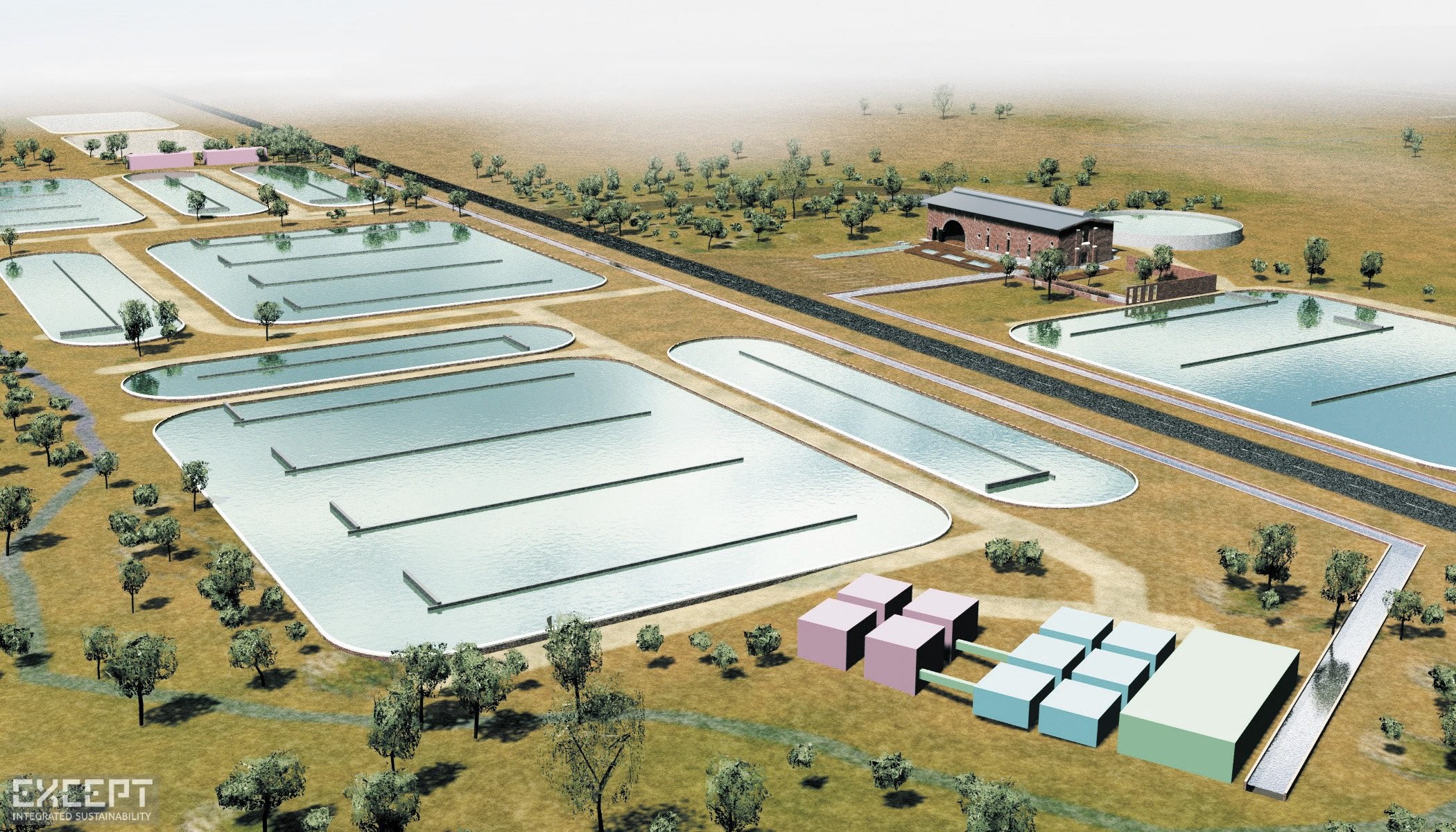

Once at the plant, the water is pumped into large shallow open ponds that are relatively easy and cheap to fabricate. The algae utilize saline water and abundant sunlight to grow - up to 30% in a day. This astonishing growth rate ensures the plant's consistent and reliable output.

Once grown, the algae are sent to the old water pump station, converted from its original use, and now houses a small freeze-drying and packaging plant, several offices, and a small visitor's center and cafe.

The spirulina algae are dried, bottled, and shipped directly to Perth. Additionally, in terms of transportation, Merredin is ideally located on the main east-west road-based trade route that stretches across Australia. This option offers a relatively straightforward opportunity for expansion and ease of transportation of spirulina products.

The algae plant has a fantastic return on investment, all within five years and with a 300% margin for error. It provides local employment, functions as a tourist attraction., and works within Merredin's saline water issues. All this aids the local government in economic development and provides a positive economic and ecological status beyond the town's limits.

The plant addresses Merredin's problems as follows:

Plant Parameters

Manpower

Raw Materials (Per Tonne of Product)

Utilities (Per Tonne of Product)

Plant & Machinery

Economics (all values in AUD)

Landscape

The Landscape design is driven largely by the functions and performance of the plant. One of the more important features of the concept is that it offers an incredible view upon arrival in the town of Merredin. The big agitator tanks reflect the sky and stretch far into the distance as viewed from the road. This increases the uniqueness and recognizability of the town, attracting more tourism.

There are no walls around the entire complex as this will obstruct the glorious views of the landscape surrounding the plant. Instead, a small moat is used to secure the complex and keep unwanted curiosity out, while also functioning as the main water supply to the tanks. The placement of said tanks is optimized to minimize the grading of the land.

Pump Station Design

Pump station number 4 was designed and built by C.Y. O’Connor in 1903. It’s a testament to the quality and dedication put forth by the early pioneers of the Western Australian desert. Restoration guidelines from Water Corporation WA allow for the change of function as required for this plan.

The new design minimizes the takeover of the pump station's original design and preserves the characteristic elements using pragmatic solutions to protect the building.

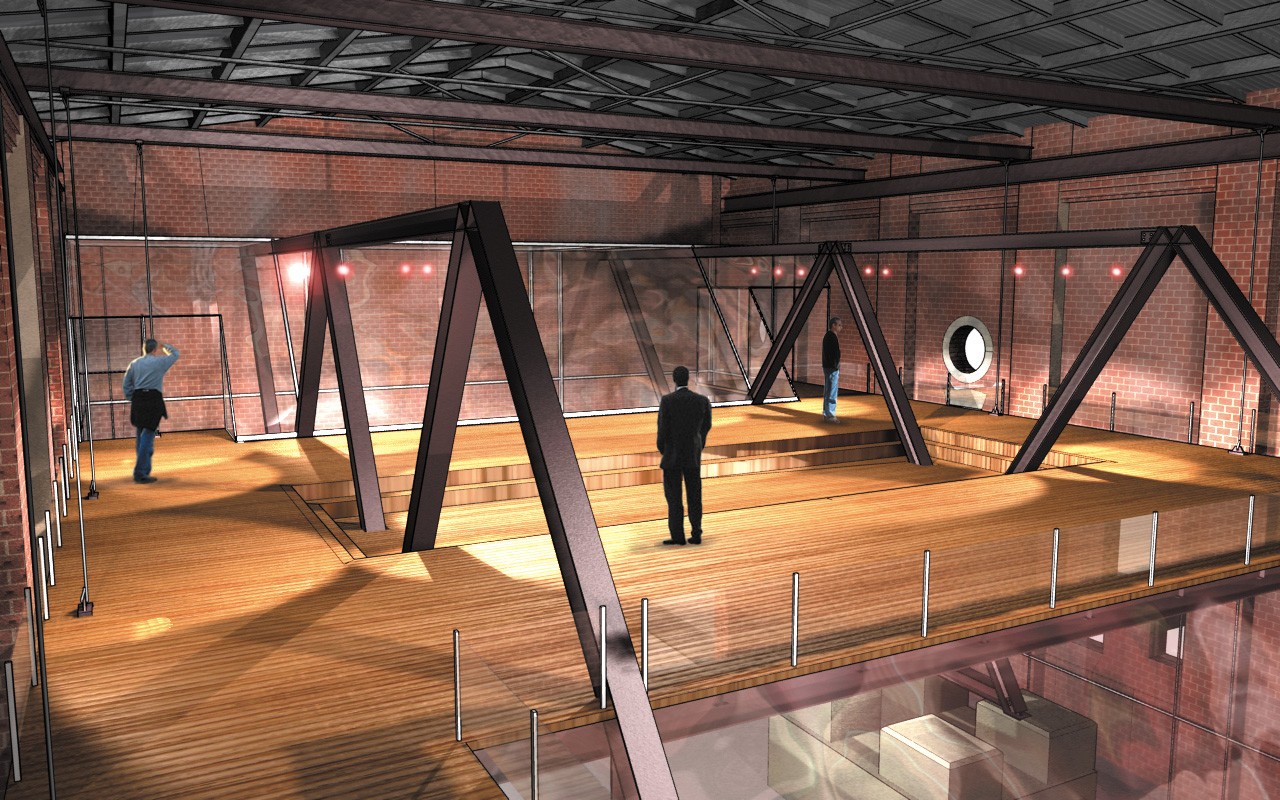

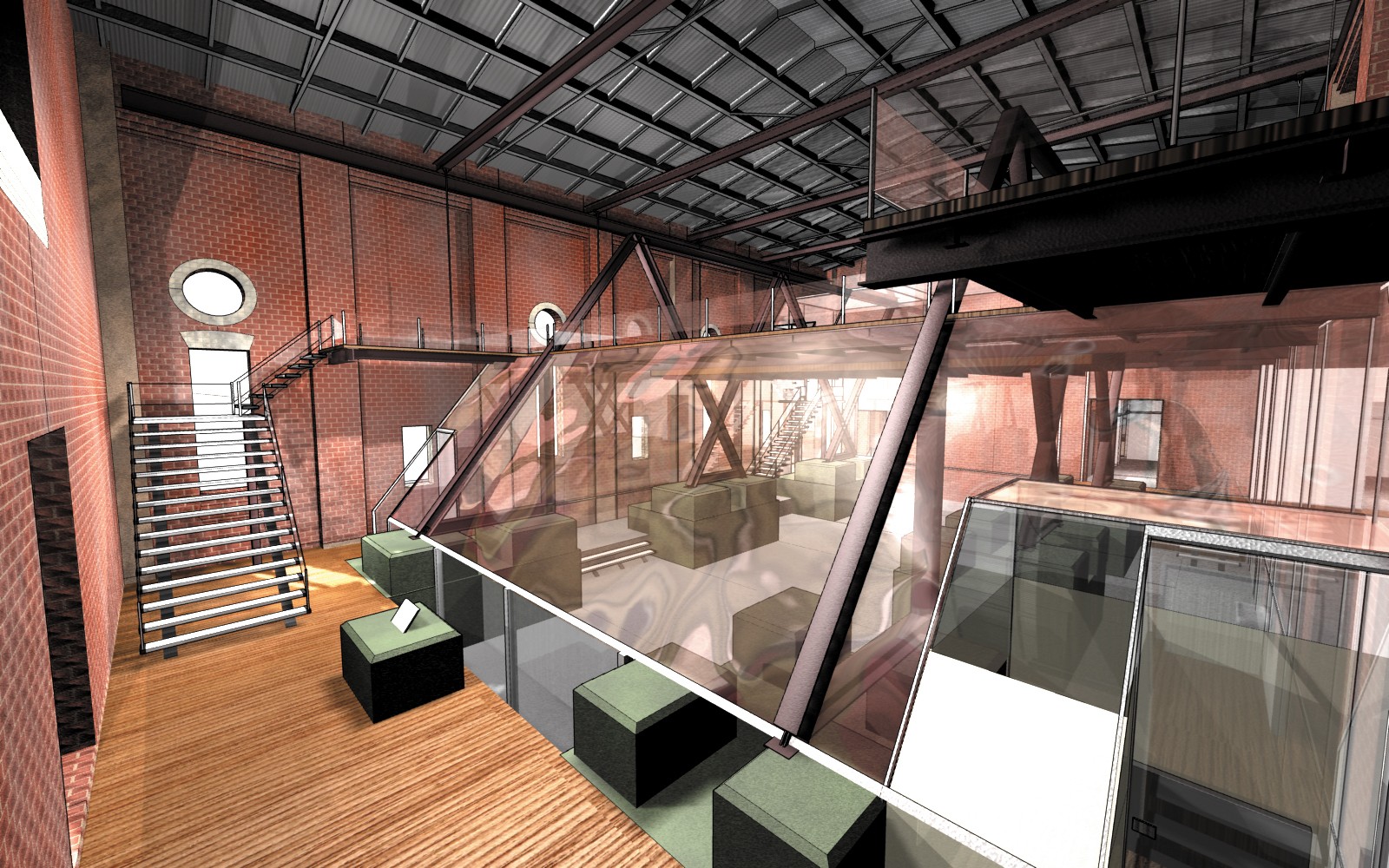

The pump station creates three spaces in one complex. The first space is a large hall measuring 22x14 meters and three stories high. A wooden floor surrounds six granite plinths, originally used to support the large water pumps. These structures now help to divide the space and also provide a framework for new elements, incorporating new machinery and administrative sections.

The two other spaces are just as high but have a smaller footprint. The middle space is an awkwardly narrow corridor, not more than 2 meters wide and 14 meters long. This area will contain some of the bathrooms for the factory and café.

The cafe resides in the third space on the east side of the building. The highlight of this space is a huge arch on the north side through which coal trains use to access the building. The new project sees this void turned into a large window to view outside.

The Merredin spirulina plant is a shining example providing insights into systems analysis, holistic design, and the merger of disciplines as diverse as economics, ecology, and design. It proves that innovative and ground-breaking solutions are possible in even the most remote and unexpected places.

We see a bright future for ecology-driven economies, systems design, and the inclusion of social aspects within development processes. By documenting this project extensively, we hope you've been able to travel with us on this remarkable experience.

June 10, 2001

Director